UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH BLOGS

The Office of Undergraduate Research sponsors a number of grant programs, including the Circumnavigator Club Foundation’s Around-the-World Study Grant and the Undergraduate Research Grant. Some of the students on these grants end up traveling and having a variety of amazing experiences. We wanted to give some of them the opportunity to share these experiences with the broader public. It is our hope that this opportunity to blog will deepen the experiences for these students by giving them a forum for reflection; we also hope these blogs can help open the eyes of others to those reflections/experiences as well. Through these blogs, perhaps we all can enjoy the ride as much as they will.

EXPLORE THE BLOGS

- Linguistic Sketchbook

- Birth Control Bans to Contraceptive Care

- A Global Song: Chris LaMountain’s Circumnavigator’s Blog

- Alex Robins’ 2006 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- American Sexual Assault in a Global Context

- Beyond Pro-GMO and Anti-GMO

- Chris Ahern’s 2007 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- Digital Citizen

- From Local Farms to Urban Tables

- Harris Sockel’s Circumnavigator’s Blog 2008

- Kimani Isaac: Adventures Abroad and At Home

- Sarah Rose Graber’s 2004 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- The El Sistema Expedition

- The World is a Book: A Page in Rwand

Yuba City Sikh Festival, Part 5: The Parade

AND NOW, THE PARADE. To start, I recommend watching the video shot from the drone flying overhead during the festival:

The beginning and end of the drone flyover shows the beginning of the parade — the starting point of my post.

The lead float of the parade is a large throne upon which the Guru Granth Sahib is seated, one that is likely modeled after the palanquin upon which the Sikh scripture is carried in Amritsar during the daily processions in and out of the Golden Temple grounds. This, however, is a full parade float that holds priest, musicians, and attendees of the Guru.

The floats that followed either commemorated major historical events in Sikh history, including the martyrdom of Guru Gobind Singh’s two younger sons (discussed in a previous post), or martyrs of contemporary Sikhism.

The center of the Khalistan agitation was a stage constructed on the side of the parade route in support of the creation of Khalistan. Chants of “Khalistan / jindabad!” (long live Khalistan — the same style of chants that India and Pakistan used leading up to and after Partition in 1947), “What do we want? / Khalistan!” “India out of / Khalistan!” alternated with cries in English for Khalistan and speeches listing what rights the Indian government is withholding from the people of Punjab.

Our float then passed the Sikh Referendum 2020 stand and continued along the route, and the cries for Khalistan faded away as the stand crawled out of sight.

My mom and I sat on a float at the back of the parade procession, and the real magic was what we saw during our six hours proceeding very, very slowly down the 4.5-mile parade route. The route was lined at every possible turn with food stands set up by gurdwaras, charitable societies, and cultural groups, all serving chai, samosas, pakoras (vegetable fritters), kulcha (small sandwiches of potatoes and garbanzo beans), sweets, Punjabi beverages, just about every Punjabi snack imaginable. People handed food and snacks up to our float, then trash bags to collect and take away our waste. The volunteers ensured no one went hungry or thirsty during the parade.

These three photos are just a small sample of what the parade offered its attendees, as the sheer number of people there stretched much farther than the eye could see. This was as pure and grand an expression of Punjab — of the Sikh pillar of seva, or selfless service — I had ever seen, and it was right in my home state of California. It drew Sikhs from all around the world, including a woman from New Delhi who sat by my mother and me on the float. Despite the political turmoil underpinning the sentiment of this festival, the most prominent feeling was the genuine sense of pride and joy that followed us the entire weekend.

The following morning, Sikhs came out by the dozens to clean up after the parade, leaving the streets of Yuba City even cleaner than they were before the festival started. As good as Punjabis are at throwing parties, Sikhs are even better at cleaning them up.

***

I’ve been sitting on this particular post for months now, mulling over what analytical framework with which I should be approaching it — is it the whole of Punjab and its vibrant culture packed into a 4.5-mile parade route? Is it Punjab showing the breadth of its global outreach, paired with its almost microscopic focus on the events of the homeland? And what about the cultural festival and its symbolism: how the festival is either an ideal of the culture it depicts or a microcosm, or both? The more I thought about how to frame the festival, the further, I felt, I was getting from it. Yet, it didn’t seem appropriate to just say, “This is Punjab,” and leave it at that.

I am exceptionally proud of my Punjabi-Sikh heritage. I have worked tirelessly for the past several years to learn the language and the faith, including two and a half years attending the Gurdwara Sahib of Chicago, a month in Ontario for the past life of this blog, and a month in Punjab for field research. My undergraduate education, largely, was a process of leaving home to find Punjab. I even returned to New Delhi after I graduated to work a job that proved unrealistic for me to take on, considering I did so without allowing myself time to recuperate after the whirlwind that was my final year of undergrad. Every Friday in New Delhi, I stood on the balcony of my apartment and called the professor I had stayed with in Punjab the previous year. Every week, as I sweated through the monsoon humidity and late summer heat, we discussed when I would be able to visit Punjab, his students, his children. “I fixed up a room for you,” he said, just as he had done the first time I stayed with him. “When the weather is better, when I get a free weekend, I’ll come visit,” I said.

Because of health reasons, I left India without making it to Punjab, and I was frustrated and disillusioned that I had traveled halfway across the world, only to miss Punjab because of weather and too heavy a workload.

I came home and saw Punjab stronger than I had seen in India — more concentrated, louder, more political. I had been to the festival six years prior, but my experience of this culture was limited due to lack of interest and decreasing exposure (read: being in high school). This time, I was in tune with the events in Punjab and their implications on the festival, with every song and speech in Punjabi, with every aspect of the festival and parade.

My family was at the first festival; my grandfather was an organizer, and my mom and her siblings walked the then 5-mile route. The turnout was marginal, and the other organizers complained about the length of the route. The idea for the parade, my grandfather said, came from a Sikh festival in Vancouver — a community that had settled in the continent decades prior. Today, with the growth of satellite television and social media, the Yuba City Sikh Festival has mushroomed in size to become the largest Sikh festival in North America. The festival represents the full spectrum of Punjabi-Sikh culture, from the idealized version of Punjab the organizers put forth, to the loud political advocacy of separatists, to the fraying edges of popular memory of Punjab among youth. Attendees see in the festival as much as they know of Punjab, whether they track daily news reports out of the home country or could care less about India and its politics. The festival is, indeed, Punjab — equally to those who never got acquainted with the home country, and to those who never really left.

Yuba City Sikh Festival, Part 4: Media and Circulation

At the back of the langar hall on the Sikh Temple of Yuba City grounds stands a wooden shelf completely filled with Punjabi newspapers. These are the same papers that pile up on the shelf beside my grandfather’s bed, newspapers that have, for years (the weight of “years” only being relative to my age), given gurdwaras and their congregants a direct line of information to the happenings in the homeland: Punjab Times (Chicago-based, founded in 2000), Punjab Mail (based out of Elk Grove, CA, an hour south, founded in 2009), Sade Lok (our people), Ajit, and so on. Then came connectivity through radio, calling cards, Internet, and television: Raza (Chicago/Toronto-based calling card company) in 1995 and Amantel (Hyderabad-based calling card company) in 2002, ZEE TV in India in 1992 and in the US in 1998, ATN Alpha ETC Punjabi (Canada-based Asian Television Network, which licenses media from ZEE TV) in 2001, JusPunjabi (Long Island-based Punjabi TV station) in 2007, Punjabi Radio USA in 2010, and an ever-expanding list of websites and social media-ites on the Internet. The spread of media has enabled Punjabis – as it has done with every major diasporic community – to grow their sense of connectedness to one another, shrinking the distance between home and homeland, community and country. I have experienced this firsthand; WhatsApp and Facebook allow me to easily keep in touch with Punjabi friends and family in Toronto, southern UK, Delhi, and Punjab, while a calling card lets my grandfather contact less tech-minded relatives and friends in the UK and Punjab – though, for him, Facebook has become a preferred means of communicating because of how effortlessly it creates a sense of network.

The segment of the diaspora literate in Punjabi has not outgrown the newspaper, however, as the newspaper remains the first line of information for the elder Punjabi. As the Yuba City Sikh festival approached, the newspapers shifted from Punjab to California, while New Jersey and New York-based television stations aired increasingly more ads of the upcoming festival in Yuba City. The local newspaper, The Appeal-Democrat, recognizing the growing significance of this 36 year-old festival, devoted several front pages to the Sikh festival and parade. The gallery of newspaper clippings below offers a glimpse of the central valley’s Punjabi community, as told through newspapers.

Before the newspaper, the gurdwara was the news hub, whether through congregants calling India and visiting, or through new immigrants reporting on the homeland. With time, access to Punjab in the household and the community has strengthened. Every week, my nanaji rushes to the gurdwara to pick up his copies of each newspaper so that he may track the goings-on in the home country. Punjabi radio provides a steady stream of Sikh religious and folk music to the household, and satellite television (for my grandparents’ house, Hindi programming) feeds them the latest soaps, news reports, cooking shows, and programs recounting the golden ages of Bollywood song, dance, and stardom. Media has filled in the gaps of the minority experience, making it easier to preserve racial identity in the household, especially for the recent immigrant. The difficulty, however, still lies in engaging those born outside the homeland, as they do not have the same stake in the home culture as their parents or grandparents. Yuba City’s annual Sikh festival, when the eyes of global Punjab, regardless of location or generation, converge on northern California is a start.

The Movie as Memory

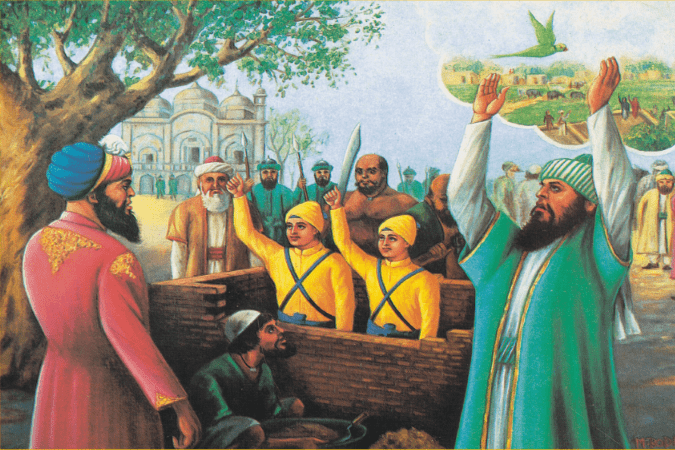

In the middle of November of 2014, I went with the families I was staying with in Mohali and Landra, Punjab, to see Harry Baweja’s animated film Chaar Sahibzaade (tr. Four Sons, Sahibzaade being a formal, respectful term for sons), which tells the story of Guru Gobind Singh’s four martyred sons: the teenage Ajit and Jujhar Singh, who died in battle protecting the Sikh fortress at Anandpur (tr: City of Bliss), and the younger Jorawar and Fateh Singh, who were captured by Sirhind governor Wazir Khan and imprisoned alive in a brick wall because they wouldn’t convert to Islam. These stories are by far the most tragic of Sikh history, as they tell of the sacrifices of children made in defense of the faith. Needless to say, there was not a dry eye in that theater.

This post is a brief departure from the Yuba City Sikh Festival, but I write it as an expansion on the recurring theme of martyrdom in Sikhism. When I return to the festival, I will discuss the Sikh parade and its floats, but the parade cannot fully be understood without first explaining how imagery like that of the chaar sahibzaade shapes and reshapes Sikh memory.

Painting of Jorawar and Fateh Singh chanting the Sikh cry for victory (jakara) as a brick wall is being built around them. From http://www.gurusgangasagar.com. Depending on what source you look at, the sons are 9 and 7, 8 and 6, or 7 and 5, with Jorawar being the elder of the two. Jorawar and Fateh Singh, in all animated depictions I have seen of the two, are shown wearing this exact outfit in these exact colors. Mass reproduction often encodes an image in popular memory until an official film is able to grant it legitimacy.

Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons – particularly the younger two – have been immortalized in Sikh memory because of the gravity of their sacrifice. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib stands in Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, built around the wall in which Jorawar and Fateh Singh were trapped. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib is among the most significant historical gurdwaras in the faith because of the poignancy of the sons’ story, but all historical gurdwaras I have visited in India (roughly twenty for me) stand in memory of a significant event or figure. For example, Gurdwaras Sis Ganj Sahib and Rakab Ganj Sahib in Delhi, and Guru Ka Taal in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, commemorate different stages of the ninth guru’s martyrdom at the hands of Mughal rulers – from his arrest to his execution to the well from which he drank before he died. Gurdwara Keshgarh Sahib in Anandpur Sahib (down the hilltop where Ajit and Jujhar Singh died), birthplace of the Khalsa, displays Guru Gobind Singh’s weapons in the temple’s inner sanctum. The idea of a gurdwara being built in honor of a person trickles down to small village gurdwaras erected in honor of a priest or significant contributor to a community, like several household gurdwaras I saw where the picture of a deceased relative sat next to the Guru Granth Sahib. Since religion, in many ways, is a process of teaching children an inherited set of values and beliefs, the story of Jorawar and Fateh Singh is particularly resonant because of how it can teach children of sacrifice and unwavering devotion to family and faith. Moreover, the chaar sahibzaade are, after the Gurus, among the first evoked in the Sikh Ardas, or major spoken prayer of the daily litany. In other words, they are among the first to be remembered:

The opening of the Ardas, from the Sikh orthodox code of conduct. The first paragraph is an evocation of the ten gurus and the sword of the tenth guru, while the second paragraph opens with a call to remember the Panj Pyare (the first five baptized Khalsa Sikhs), the Chaar Sahibzaade, and the Chalhiaa Muktiaa, or the forty Sikhs who died in battle in Muktsar protecting Guru Gobind Singh.

Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons also provide the faith with the first story it can depict on screen. The orthodox administration of Sikhism, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) prohibits live or animated depictions of Sikh Gurus or any form of divinity (similar to contemporary conservative Islam and its policing of depictions of Muhammad). For example, the SGPC in early 2015 protested Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh’s film MSG: The Messenger over the DSS chief’s claim of prophethood. Chaar Sahibzaade director, in an interview with Times of India, explained how arduous the process of approval by the SGPC was for him, saying, “I was adamant and after making 80 trips to Amritsar managed to convince them.” Baweja added, “They [the SGPC] had agreed that while I could not touch the 10 gurus, I was allowed to show the boys.” Consequently, the opening credits of Chaar Sahibzaade list several pages of permissions granted by leaders in the Sikh panth, and all images of Guru Gobind Singh, despite movement occurring around him, are static. The trailer, which first attributes the SGPC, gives a glimpse of how carefully Guru Gobind Singh (whose image is based on the already ubiquitous painted image of the Tenth) is shown in the film:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CSlNf70SFi8

(And my favorite line in the film, at 1:00 in the trailer:

Wazir Shah’s courtier: “Tuhanu mauth to dar nahi lagda?” Do you not fear death?

Fateh Singh: “Tuhanu Quda to dar nahi lagda?” Do you not fear God?)

The film, finally, brings us back to Yuba City and the following float, which uses the images of Jorawar and Fateh Singh as they appeared in Chaar Sahibzaade. Because of the SGPC’s approval of the film, any image used from the film can be treated as though it has been canonized:

A float showing cardboard cutouts of Jorawar and Fateh Singh being encased in a cardboard brick wall.

After a convoluted, zig-zaggy exposition, I am brought to the point of the post: Sikhism is a process of remembering – of remembering the name of God, the martyrs of the faith, and so on. It is not necessary to delve into Khalistan and the countless Sikhs disappeared by Indian police to bring this point across, because the sacrifices of Sikhs date back to the Gurus (Guru Arjan, the fifth, and Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth, were executed by Mughal rulers, while Guru Gobind Singh was assassinated by an Afghan). As Brian Keith Axel (2001: 151) notes in The Nation’s Tortured Body, violence against the male Sikh body – the body that has adorned turban and beard and bracelet and dagger – is akin to violence against the global Sikh body, as the devout Sikh is the image of purity. The chaar sahibzaade show that violence and the nobility of martyrdom exist deeper than in the body of the pure man, but in the even purer body of the child. The inviolable spirits of Guru Gobind Singh’s children – when their father was still the living center of the faith – gave their lives in defense of the faith: Ajit and Jujhar Singh in battle, but Jorawar and Fateh Singh without spilling a single drop of blood. However, this story and its message of sacrifice only gained as much traction as it has once it was depicted on screen; this film is not the first to depict the chaar sahibzaade, but its success among global Sikhism shows how Sikh history and hagiography have slowly been migrating to the screen. Though the lives of the gurus, too sacrosanct to be approached, remain in reproduced paintings and grandmothers’ tales, their spiritual successors may finally be portrayed in a changing medium: from story, song, and picture, to film. Because they have been digitally immortalized (in a film approved by the SGPC), these sons need not fear their story be distorted by memory.

When these images are evoked in the context of Khalistan or a diasporic parade, their significance changes. For Khalistan, Guru Gobind Singh’s four princely sons argue that self-determination is a struggle that has existed in Sikhism since the time of the gurus, predating Karnail Singh Bhindranwale in the 1980s and the Akali Dal cry for Azad Punjab (sovereign Punjab) prior to Partition. Self-determination, to the separatist, is a pillar of Sikhism. To the diaspora, however, the significance of the memory shifts. Instead of the chaar sahibzaade embodying the young blood of Khalistan, they represent the stories that Sikhism cannot let its children forget. As each generation passes its selective memory and cultural amnesia onto the next, Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons remind the faithful of everything their predecessors fought for to ensure their beliefs would survive. Orthodox Sikhism anticipated this process over 100 years ago, so Sikhism has become, consequently, a process of official memory. This meticulous process of canonizing stories has allowed the faith to retain common points of reference across countries and continents. In other words, if you evoke Guru Gobind Singh’s four martyred sons, the image that comes to mind – much like Daniel Radcliffe being the face of Harry Potter or Robert Downey, Jr., for Iron Man – will inevitably be from Harry Baweja’s animated film. The movie is the memory.

Yuba City Sikh Festival, Part 3: The Generation Gap

“If immigration stopped tomorrow, these gurdwaras would be empty,” foretold Nandeep Singh, co-founder of Jakara Movement, in his presentation titled “Why Don’t We Care About Our Kids?” Jakara Movement is a non-profit organization dedicated to spreading awareness of Sikhism and Punjab among Sikh youth in the US, though the elders filling out Dashmesh Hall on the Sikh Temple of Yuba City grounds gave little credence to the young upstart’s claims.

This post will take us through the remaining three speakers of the Sikh Seminar discussed in the previous post, centered on what is one of the Sikh diaspora’s most pressing issues: can the faith survive outside of its homeland? And, as an extension of that question: if Sikhism is to survive as a global religion, what elements of its home culture must be preserved? Punjabi language? Punjabi literacy? Cuisine, fashion, gurdwara attendance, marriage within the culture? Popular sociology maintains that immigrant culture cannot survive three generations in a new country, but the Internet and social media have created a niche for any and every community that has access to it. My generation (meaning my brother and first cousins) is the first in my family to be born entirely in the US. Of the seven of us, five of us speak Punjabi, four of us are half (my brother and I being the two halfsies who speak), and only one of us can read Punjabi. At what point will it be inevitable that we lose Punjab?

And now, the speakers.

Sikh Seminar and Open House, October 31, 2015. In this post, I will focus on Sikhnet.com Founder Gurumustuk Singh, Jakara Movement Co-founder Jakara Movement, and Journalist Jarnail Singh.

1. Gurumustuk Singh, Founder, Sikhnet.com: Sikh Perspective on Meaning of Universal Sikhi Values.

In truth, my notes on Gurumustuk Singh were sparse, because my focus going into the festival was how the festival reflected Punjab and its diaspora. Gurumustuk was born in Los Angeles, was raised Sikh, and was schooled in India. His parents – a Christian father and Jewish mother – found Sikhism through Kundalini yoga and meditation. They represent a small contingent of primarily non-Punjabi Sikhs known as 3H0 (Happy, Healthy, and Holy Organization), and their home base is in Espanola, New Mexico. SikhNet, which is one of the most prominent sites devoted to spreading awareness about Sikhism, is also based out of Espanola. 3H0’s philosophy is to live spiritually and cleanly through yoga, contemplation on the name of God (as Guru Nanak preached), and particular practices of natural food and dress, not unlike the Hindu concept of ayurveda (3H0 has their own line of natural foods, oils and clothes). 3H0 was founded by Harbhajan Singh Puri (known to his followers as Yogi Bhajan), who moved from India to Toronto in 1968 and taught about the lives of the Sikh gurus as part of his yoga classes. He devoted his life to teaching yoga and spreading the name of God as detailed in the Guru Granth Sahib, or Sikh scripture.

(My side observation, not to diminish the value of 3H0 in any way, is to point out how India is a strong breeding ground for religious/lifestyle movements founded by people preaching yoga and meditation, some of which take root in the US. See also: Patanjali and his line of all natural products, Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati and ISKCON, Shah Mastana Ji Maharaj and the Dera Sacha Sauda “Confluence Of All Religions,” Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and transcendental meditation, and so on.)

SikhNet provides a powerful source of cohesion for converts to Sikhism, and it is an excellent starting point for delving into Sikhism. Though their stories are more derived from oral tradition than from historical sources (scrutiny courtesy of my grandfather), these stories depict Sikh popular memory of its heritage – how popular Sikhism strives, rather optimistically, to see itself when separated from politics. It’s quite a difficult ideal to implement.

2. Nandeep Singh, Co-founder, Jakara Movement: Why Don’t We Care About Our Kids?

Nandeep Singh is a Sikh from Fresno, California, whose presentation explained how US-born and Indian-born Sikhs are “poles apart.” Singh argued that Sikhism is disappearing among its American-born youth, as their parents, through lack of engagement with their children, are not doing enough to preserve Sikh culture. His presentation came with charts that detailed Sikh youth attendance in temples:

Until the teenage years, parents bring their children to the gurdwara on Sundays, as seen by attendance at gurdwaras in San Jose, Livingston, and Fresno, California. Teenagers’ attendance numbers drop sharply, as the vast majority of gurdwara attendees are the parents of those children and the generation above. Singh noted that 1/3rd to 2/5ths of this children are born in Punjab and immigrate to the US, so the problem is not just US-born youth. He calls this current generation of Sikhs (my generation) the lost generation. Interest in Sikhism is not cultivated through basketball and bhangra, but through community building efforts organized around Sikh values. This model of youth engagement – religious school, youth groups, scholarship programs, and so on – focuses on making youth proud of their Sikh heritage, a heritage that emphasizes the need for learning the Punjabi language and maintaining a political awareness of the happenings in Punjab. In the absence of any central Sikh unifying body (India has the SGPC, but Sikhs outside India have no overarching administrative body), Jakara Movement strives to create a sense of cohesion among American Sikhs.

The crux of Nandeep Singh’s presentation was his observation that there were no youths in the audience of this seminar. The kids were playing outside with one another, looking at the shops and toys, making no clear effort to learn about political upheaval in Punjab and its implications on Sikh identity. Any person under the age of 25 in the audience (e.g. me) was an exception to a trend of detachment from their parents’ culture, implying that (to answer my opening questions), Sikhism needs an all-of-the-above strategy to keep its culture alive: language, literacy, physical Sikh markings, and so on. In other words, ours is a path from which we cannot stray. We must wear our identity proudly.

3. Jarnail Singh, Journalist and Member of Legislative Assembly, Delhi (Aam Aadmi Party): Challenges Before Sikhs And How to Overcome Them

Jarnail Singh came more than hour late, as he was coming to this conference straight from India. He spoke entirely in rapid-fire Punjabi, quoting Sikh scripture and berating India’s major political parties, from the far right-wing Hindu RSS poisoning Punjab with heroin to Punjab’s own lack of political cohesion. Punjab is on track to becoming a failed state, from farmer suicides to drought to cancer and drug addiction. In a video I did with formerly-Chandigarh-now-Austrialia-based video artist Bobby Sandhu, Sandhu notes that Punjab is ashamed of how its culture, and how it is rare to find people who are proud to be Punjabi. Jarnail Singh echoed this sentiment. Punjab has no central administration, no think tank to ensure that it and the Sikh faith will survive in India. Punjab and its diaspora, instead, can only seem to watch as the province dries up.

***

When it came time for Q&A (which was actually before Jarnail Singh arrived), I asked Gurumustuk and Nandeep Singh if they think Sikhism can survive in the US without the Punjabi language. Gurumustuk said that he could not imagine his life in Sikhism had he not grown up in Punjab, while Nandeep Singh flatly said no and that it is the responsibility of our generation to decide how Punjab will look in America. The previous questions in the session had been primarily from elder Punjabis asking Manoj Mitta about the province of Punjab, with little attention being directed to the state of Punjabi youth. As Nandeep Singh noted, “How can we think about the situation in Punjab when we don’t think about our kids?”

The generation gap is the most confounding issue facing Punjab, as it has been for every immigrant community in the US before. Immigrants tend to preserve as much as they can of home. In the case of Punjab, this was done by maintaining monetary ties to home; much of Punjab, including its largest gurdwaras, was developed by foreign money brought back in to the province: immigrants to London, Toronto, Vancouver, New York pursuing wealth through business, law, engineering, or medicine and sending funds back to their home villages. These veritable castles dot village roads throughout Punjab, their gated confines facing crumbling roads and straw huts caked in cow patties. Those who left India decades ago and have not returned – for me, my family and the Punjabi families my research has guided me to – note with heavy sighs that they would not have the same opportunities in India as they have had in the US and Canada. The original waves of Punjabis to California of the 60s, but dating back to the opening decades of the 20th century, adopted America, taught their kids America, and now fear that their grandchildren do not know Punjab. In many regards, their fear is true; the language is disappearing, and knowledge of Sikhism is going with it. Congregations are filled out by new waves of immigrants who have been displaced by 1984, by the increasing difficulty of farming in light of pesticide-resistant bugs, in search of greater economic opportunity, but the children of Punjab have grown up with their parents protecting them from these realities. The generation gap is stark and massive, accelerating with each new generation but met with artists and organizers who work that much harder to figure out what Punjab means as the memory of mustard fields fades further into the distance.

Yuba City Sikh Festival, Part 2: The Politics

Now, anyone who read this blog in its past life knows that I love politics, especially Punjabi politics. It is with this in mind that we turn to the Yuba City Sikh Festival and a seminar that was held in the Dashmesh Hall (meaning Hall of the Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh). First, we must talk about Punjab.

On October 12, 2015, 112 pages were found torn from the Guru Granth Sahib (the living Sikh scripture) in Bargari, Faridkot, Punjab. This was an early incident in a series of desecration events throughout the province, events that sent shockwaves throughout the Sikh world. See the map below:

A map of Punjab indicating where desecration events took place, starting October 12 and continuing over the few days.

1: Bargari, Faridkot district (mentioned above)

2: Kohrian, Faridkot district

3: Mishriwala, Ferozepur district

4: Ludhiana

5: Gurusar Mehraj, Bathinda district

6: Sarai Naga, Muktsar district

*: Baghapurana, Moga district

Events 1 through 6 were detailed in an article on Firstpost, though the most significant desecration event (*) occurred in Baghapurana, Moga district, on October 14. Here, police fired on a peaceful protest to disperse it, injuring 80 and killing 2. Protests erupted throughout North India blaming Chief Minister of Punjab Parkash Singh Badal for turning his back on Sikhs, as well as the Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS), a political/religious/charitable group operating out of North India. By the time the story reached Yuba City, Badal was the main target of outrage:

#BoycottBadal was the theme of this stand at the Yuba City Sikh Festival, where passersby could hit a dummy of Chief Minister of Punjab Parkash Singh Badal with a sandal. In South Asian culture (exactly like the infamous Iraqi journalist who threw a shoe at President Bush), hitting someone with a shoe is among the most blatant signs of disrespect possible. Feet are culturally unclean; to show respect for someone, you bow at their feet and take up their dirt, so hitting someone with a shoe is like weaponizing all the uncleanliness your soul has ever tracked, this life and beyond.

(On a sidenote, the DSS is a fascinating entity; they consider themselves a spiritual successor of Guru Nanak, founder of Sikhism, and they argue that there is no distinction between religions – Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Christianity, and so on. Their current leader, Saint Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Ji Insan, is a cult of personality figure who stars and directs his own action/religious film series, MSG – The Messenger of God. Even his name is an overt effort to unite faiths: Saint being Christian/Sufi, Gurmeet meaning “of the Guru,” Ram being a Hindu name for God, Rahim “the merciful” being a name of God in Islam, Singh being the Sikh male last name, Ji for respect, and Insan from Arabic, meaning human.)

It is with this in mind that we turn to the seminar. This post will cover the first two speakers.

Sikh Seminar and Open House, October 31, 2015, 1 PM to 3 PM (though it ran until 4:30). The speakers: Delhi Journalist Manoj Mitta, Activist Daughter Navkiran Kaur Khalra, Sikhnet.com Founder Gurumustuk Singh, Jakara Movement Co-founder Jakara Movement, and Journalist Jarnail Singh.

1. Manoj Mitta, Journalist & Author of When a Tree Shook Delhi: “1984 Carnage and its Aftermath”

1984 (referenced in an earlier post, “Symbols of Sikhi”) is a watershed year for Sikhs. It was in 1984 that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, in an effort to eradicate a Sikh separatist movement in Punjab, ordered a coordinated attack on Sikh temples throughout Punjab and North India, including the wholesale destruction of Akal Takht Sahib, one of the five holiest gurdwaras in all of Sikhism. Operation Bluestar killed Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale – an extremist to history, but a martyr to Sikhs. After the operation, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards.

In November of 1984 (Mr. Mitta pointed out that this festival was the 31st anniversary of this event), Indian police launched a coordinated attack on Sikhs throughout Delhi and Punjab in retaliation. The Indian government maintains that these were riots were nothing more than public manifestations of anger directed at a specific religious group (of which India has a long history), but Mitta argued that the events that opened November 1984 were too big to be just anger. Official reports state that 2733 were killed in three days of violence, and that the police actively recruited people to riot, that they entered neighborhoods, spread word of the riots, and catalyzed the violence. The ensuing act-finding inquiry included no public hearings, no testimonials by prominent victims, no justice. Mitta’s book, When a Tree Shook Delhi, released in 2007, took 23 years to write – a testament to how difficult it was, and still is, to piece together 1984.

2. Navkiran Kaur Khalra, Daughter of Internationally Acclaimed Human Rights Activist Jaswant Singh Khalra: “How to Honor My Father’s Legacy”

Navkiran Kaur Khalra’s father spent his life fighting for the Indian government to acknowledge the atrocities of 1984 and after. For the decade-plus following ’84, Punjab was essentially a police state. Blockades dotted every major highway, and bodies turned up at crematoriums, stripped of any form of identification. According to Indian law, a body cannot be cremated without permission of the deceased’s family, but ledgers at Amritsar crematoriums in 1989 reported that 6,000 bodies were cremated due to lack of identification. 297 had been identified, but the government claimed that they were missing to cover up police involvement. Khalra’s father, who went missing in 1995, was one of an estimated 25,000 who were disappeared in the years following 1984. The CBI (India’s FBI) took 12 years to convict 6 people involved in the disappearance and presumed murder of Jaswant Singh Khalra.

These are familiar stories to the Sikh diaspora, stories that have driven – and are still driving – the faith out of Punjab. The popular memory of violence and repression solidifies global Sikhism’s resolve to form a nation of their own comprised of lands their kingdom once controlled before it fell to the British. These lands stretched as far north as Afghanistan, past Shimla in the east, the Thane River in the west, and on Delhi’s door in the southeast. Today, by contrast, Punjab is a province carved from a region that once included Pakistani Punjab, the mountains of Himachal Pradesh, and the Hindu mythological battlegrounds of Haryana. As it shrinks under pressure in India, its global voice becomes ever louder. The events of 1984, of Punjab the police state, of October 2015, hung heavy on the minds of Sikhs at the festival.

This tent commemorates those who were disappeared by police in Punjab in the ’80s and ’90s. Pictured on the tent banner are Bhai Gurjit Singh and Bhai Krishan Bhagwan Singh, the two Sikhs killed by police in October protests – “Diamonds of the Qaum,” or global Sikh nation (qaum from Persian etymology). The cutout is of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. To the right of the cutout is a banner that reads “Disappeared by the police: Victims of Government Repression.” The photos on and in the tent show pictures of murdered Sikhs, but without proper documentation: no names, dates, locations, anything. The sparsity of solid evidence is a primary reason why the Indian government has been able to deny responsibility for so long.

Yuba City Sikh Festival, Part 1

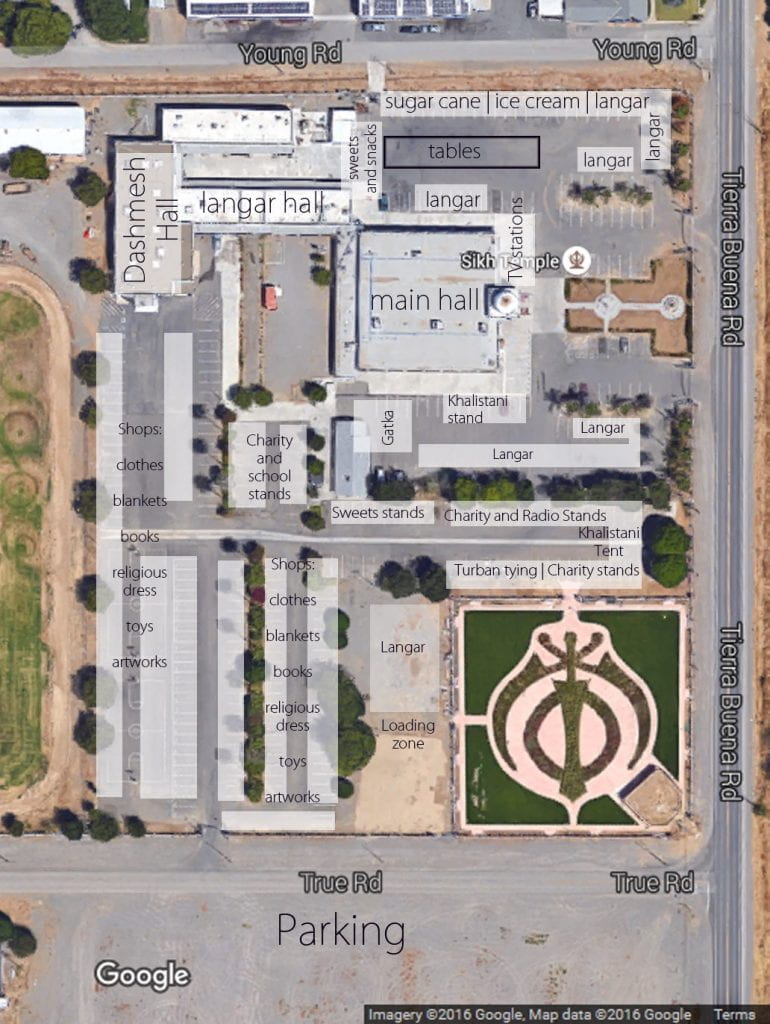

I must confess this synopsis is months overdue, and that this particular post is weeks overdue (I’m not doing so well at my one-post-a-week average), but I’m about to take you on a tour of a festival that took place at the Sikh Temple of Yuba City, est. 1969, on the closing weekend of last October. There will be a map, pictures, and foreign words that I will define for you.

November 1, 2015, marked the 36th annual Yuba City Nagar Kirtan, or Sikh festival and parade that draws roughly 100,000 Sikhs from all around the world to this small Northern California city. The parade, of course, is the main event, but the festival, held on the temple grounds of the Sikh Temple of Yuba City, is a treasure trove of its own. Vendors, charitable organizations, political foundations, media companies, and other gurdwaras erect tents throughout the temple grounds to provide free meals to festivalgoers, catch up on and debate the political happenings of Indian Punjab and global Punjab (though, as diasporic communities tend to do, they focus mostly on the homeland), and buy and sell clothes, art, books, and so on.

Let us begin the photo tour.

To avoid getting completely lost, I’ll work from the top and move down.

1. Sugarcane was provided courtesy of the Sikh Temple of Live Oak in the town just north of Yuba City. Sugarcane is a staple crop of Punjab, and sugarcane juice is a preferred summer beverage of North India, especially during the summer months (having been to Punjab and lived in New Delhi during the summer, I can attest this is true). The stalks are put through a grinder, squeezing the juice. See below:

The sugarcane grinder in full swing. The juice is mixed with lime and served in Styrofoam cups, the choice cup for all of global Punjab.

2. The ice cream was soft serve.

3. Langar, or the Guru’s free kitchen, is one of the cornerstones of the Sikh faith. Langar has been a central element of the religion since Guru Nanak (1469-1539), and his wife, Mata Khivi ji, was one of the early distributors of food. The practice continues today, and most gurdwaras are equipped with large enough kitchens that food is prepared all day long. The meals are standard Punjabi vegetarian food (vegetarian so as not to exclude any other religious community for dietary restrictions), – lentils, flatbread, a yogurt dish, a vegetable dish, some sweet dish – though for special occasions like Nagar Kirtan, the full array of Punjabi snacks emerges: pakoras (fried vegetable fritters), samosas, sweet chili flavor Doritos, chili cheese flavor Fritos, and so on. All langar, of course, is free (I would have not made it through college otherwise).

Frontal view of some langar tents. Note the allusion to martyrs – this is a central idea in contemporary Sikhism, especially in relation to the Indian government.

Alternate angle of langar tents. The banner on the right reads “sarbat da bhala,” – may good come to all – which is the closing line of the faith’s main prayer, the Ardas. On right, the banner reads “Guru ka langar” – the Guru’s free kitchen.

4. Dashmesh Hall is a separate hall that holds parallel service when the main hall is at capacity. It also hosted a lecture series during the festival weekend, which I’ll discuss in a future post.

5. The TV stations represented at the festival (aside from Mike Luery of KCRA 3 news on the day of the parade) were all offering Punjabi channel packages through Dish TV: Alpha Punjabi, Jus Broadcasting, TV 84, etc. The media companies offering these packages are based mostly out of the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, where a considerable segment of the Punjabi contingent in America lives. Satellite television is one of the main sources of cohesion among just about any diasporic community, as Punjabi TV offers a major platform for reporting on the homeland, broadcasting prayer services from Amritsar, and promoting local events, stores, concerts, etc. Television (for the masses) and Punjabi newspapers (for those still literate in Punjabi) provide the community some of its strongest sources of cohesion and connectedness to home.

6. The Khalistan Tent and Khalistan Stand will be discussed in a future post.

7. Gatka, or a major form of sword-based martial arts in Sikhism, was held on a small square of the temple grounds during the day of the festival. Of course, PVC pipe painted silver was used instead of actual swords.

Gatka held on the final day of the festival (Sunday, November 1). The previous day (Saturday, October 31), a day-long gatka tournament was held elsewhere in Yuba City, but I was not able to attend.

8. The charity stands represented charities in both California and Punjab, from local outreach groups to a home for orphans in Ludhiana, Punjab.

9. The shops are the main draw of the temple grounds during festival week, particularly the blankets (which my cousin says are great because they aren’t prone to pilling in a Sikh’s mane). Other products include graphic tees and sweatshirts that honor Sikh martial character, Punjab and its martyrs, the dream of Khalistan, and so on (the t-shirts might be subject matter for a future post, if I’m inclined).

The blankets were the main draw of the shops. They came in a wide array of designs and patterns, including floral prints, animal designs, and a 49ers print (though I told my cousin to not get a 49ers blanket because it would leave him cold).

Another angle of the shops. The Amritsar Jn. sign is a reference to Amritsar’s main train station, and, in India, trains are the people’s form of transit (unless you’re traveling within Punjab, then it’s the bus).

10. I make special mention of turban tying because the tent was organized by my own family. My cousin Tejinder organized a team of turban tying experts who measured, cut, stretched, and washed fabric so it could be tied on each passerby as a fresh turban. Local newspaper Appeal-Democrat posted a video of the process as well: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zcu71dixrcs.

Me, getting a turban tied. Directly behind me is Tejinder, sporting her remarkably fly orange-and-purple suit.

That’s a wrap! There will be several more posts to come about the happenings on the temple grounds, along with a discussion of some happenings in Punjab that underpinned the political mood of the festival. Stay tuned.

Punjab-upon-California

Hello, readers. It has been many months since last we spoke, so I wanted to update you all on where I am these days. I am in California on a gap year and am taking full advantage of the chance to move freely about my home state, which is home to one of the largest contingents of Sikhs in North America. The pictured billboard is southbound Highway 99 about 45 minutes past Fresno. The text in Punjabi reads, “Trucking insurance, good sir!” (Bhai ji translates more accurately to “bro” or “man,” but “good sir” seemed more appropriate to me.) I took this photo while en route to Los Angeles two days ago, and there was no such billboard on that route when last I went to LA in 2010. Highway 99 today has a fair share of Sidhus, Gills, Khalsas, and Manns painted on its freight trucks, and this sign is testament to their integration in the industry.

As I did in Toronto, I will use this blog to paint a picture of Punjab in California, from the annual Sikh Festival in Yuba City, to roadside signs like the above, to Punjab as it appears on television (e.g. Alpha ETC Punjab, TV84, and Jus Broadcasting). This is an older community than that of Toronto, and it does not pledge the same allegiance to the Indian tricolor that Canadian Punjabi does. Californian Punjab is elders who have renounced India to make America their home and youth who know little of their grandparents’ culture beyond bhangra and graphic tees of lions and warriors.

Since last we spoke, I studied abroad in India, graduated from Northwestern with honors (“Rappa Dappa Dappa,” as my mom calls it), and held a job in New Delhi. Parminder Singh, much to his eventual relief, did not get the Liberal Party nod for Member of Parliament in Brampton, and he and his wife welcomed their second child into the family earlier in the year. My grandfather, the great writer Mohinder Singh Ghag, just returned from Punjab on his first visit to India in over 30 years, where literary figures honored him for his contributions to Punjabi literature.

I return to this blog to do my small part to give voice to the Punjabi-Sikh experience in America, as we are a people too often conflated with the radical Islamist terrorist. In this time of renewed Islamophobia, it is crucial to celebrate every facet of America’s tapestry, regardless of race, religion, gender, creed, politics, or sports team.

A Final Reflection

I am not sure how to adequately sum up the experience of the last eight weeks. My paper will attempt to do that, but it will be formal and rigorously constructed. It won’t capture the joy I felt getting the experience of my dream job for a little while, the excitement of living in a new city, the perfection of each orchestra I sat in or heard from the house.

I head to LaGuardia tomorrow for a 1:15pm flight. In about 15 hours I’ll be back in Evanston getting back into the rhythm of college life and preparing for senior year. I have never been more motivated to make the most out of my Northwestern experience after seeing the level I need to be at if I want to succeed in this career. I will be playing more lessons and classes, sightreading on my own for at least an hour every day, and doing freelance and show work constantly throughout the year. I’m excited to challenge myself and continue to grow so that when I move to NYC in a little less than a year, I’ll be ready to dive in head first.

Tonight, for my last show I saw The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Though not a musical, it was a really unique and fitting end to my time in New York. I held onto every moment onstage as it happened, and it gave me tremendous closure. What a beautiful play. I feel ready to leave this city a better person. I’m not too upset about leaving because I know I’ll be back. I am so thankful for the opportunity to conduct this research, and I look forward to refining my research paper over fall quarter!

Thanks for reading!

Casey

“In the Room Where it Happens”

Sitting in the Hamilton pit was indescribable. To be “in the room where it happens” of one of the biggest smash hits to come to Broadway in recent years was so exciting. I had a copy of the score to follow along with and a great view of the entire orchestra. Hamilton was the eighth of eight shows I will observe from the pit in New York. In total, they were Amazing Grace, Kinky Boots, The Book of Mormon, On the Town, Something Rotten!, Les Mis, Wicked, and finally Hamilton. It still feels like this has all been a long dream. Though I am in a way dreading leaving this dream project, I am also very excited and ready to come back to Evanston.

I have absorbed so much information for my research project, but also for how I am going to run my own orchestra in the fall. I am music directing and piano-conducting a fall show and I have learned so much about how I will lead this group of players differently than I’ve ever done before. I used last year as a way to learn from others and assist/play in pits, and now I’m looking forward to a year of leadership and big steps forward in my process. I have a major project lined up for each quarter and then many options for the summer. It’s a very exciting time in my life and I can’t wait to apply what I learned on this extraordinary experience.

I will post at least once more before I leave with a final reflection.

Wrapping Up

My friend Bex was here for a few days and I haven’t posted as much because we were so busy.

I sat in Les Mis and Wicked in the past week. Both were amazing experiences because I know both scores so well. The level of sound from Les Mis was fantastic because they do not use any headphones and listen to each other. Volume augmentation is used limitedly and the group is forced to listen and naturally adjust their levels. Wicked was just stunning- the player I sat next to has played the keyboard 3 book since opening night. Over 12 years! He is fully memorized and plays the show like clockwork.

Tomorrow, I am observing Hamilton. I head home on Friday. It’s been an unforgettable experience. I submitted my Final Report that summarizes my project, and I’ll be working on my research paper throughout fall quarter. I’m going to see a few more shows and go to the library a few more times before I leave. It will be so hard to go, but I’m ready to head back to Evanston for another fantastic year!