UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH BLOGS

The Office of Undergraduate Research sponsors a number of grant programs, including the Circumnavigator Club Foundation’s Around-the-World Study Grant and the Undergraduate Research Grant. Some of the students on these grants end up traveling and having a variety of amazing experiences. We wanted to give some of them the opportunity to share these experiences with the broader public. It is our hope that this opportunity to blog will deepen the experiences for these students by giving them a forum for reflection; we also hope these blogs can help open the eyes of others to those reflections/experiences as well. Through these blogs, perhaps we all can enjoy the ride as much as they will.

EXPLORE THE BLOGS

- Linguistic Sketchbook

- Birth Control Bans to Contraceptive Care

- A Global Song: Chris LaMountain’s Circumnavigator’s Blog

- Alex Robins’ 2006 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- American Sexual Assault in a Global Context

- Beyond Pro-GMO and Anti-GMO

- Chris Ahern’s 2007 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- Digital Citizen

- From Local Farms to Urban Tables

- Harris Sockel’s Circumnavigator’s Blog 2008

- Kimani Isaac: Adventures Abroad and At Home

- Sarah Rose Graber’s 2004 Circumnavigator’s Blog

- The El Sistema Expedition

- The World is a Book: A Page in Rwand

Daichi wo Mamuro

After racing in a giant circle across the Bangkok airport, accomplishing none of my wifi dependent tasks I hoped to do before my second (this) flight, I’ve finally just sat down at the same seat I got out of about half an hour. To clarify, my airport lap was not accidental: it was necessary to re-board my Singapore-bound flight for its Bangkok-Singapore leg. The flight was delayed for a few hours in the Narita airport this morning, which effectively turned my expected two-hour layover into a two-minute layover. During those two minutes, I managed to buy overpriced airport dried mango in attempts to combat the overpriced water onboard Scoot Airlines and lack of functioning water fountain in the airport. (The credit card limit at the store next to my gate was $10, so I had to buy mango + water to get the water before boarding.) At least Scoot airlines will never get my $4 for a bottle of water….

Today, however, began on a much more pleasant note. I began the day with an early morning run through some rice paddies about 20 minutes away from Narita Airport (adjacent to the airport hostel I stayed at last night). While I’ve seen many rice paddies in Japan in the past two weeks, I couldn’t help giving some extra thought so how these Narita paddies contrasted the few miniature (adorable) rice paddies I’ve seen on multiple rooftops in Tokyo . And how much more similar these expansive paddies were to the ones I’ve biked through in Milan’s South Agricultural Park about a month ago, now. As I’ve just surpassed the halfway mark of this summer’s trip, the similarities and interesting comparisons between my research in each city are cropping up everywhere (pun intended). I’m finding it more and more difficult to not interrupt my interviewees to tell them about a similar story in Budapest or how well they’d get along with some of my Milanese research contacts.

Escalator the Odaiba City Farm (7th floor of a mall on a man-made island full of malls, next to the bowling alley)

So, while I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again: it consistently astounds and excites me how many similar stories of social, political, and environmental movements to develop local food systems (LFS) have occurred in parallel across the world. This summer, I’ve spoken to politicians, researchers, activists, business owners, and consumers who all recognize and seek to propagate the importance of urban residents connecting/reconnecting with their food sources. That connection/reconnection to one’s food sources can manifest in many different ways: e.g. through establishing direct consumer-producer relations, by growing one’s own food, or even by simply noticing domestic and regional labels in the produce aisle of a supermarket. Yet no matter what form of LFS I’ve been studying this summer, I’ve been continuously reassured that understanding where one’s food comes from is for some reason imperative in securing an economically viable, socially just, and environmentally friendly food system.

However, as inclined and motivated as my research contacts around the world are to advance LFS development, not all people share the desire and/or economic privilege to support LFS’s growth. Of course, that fact is a key motivator of my research: this summer, I hope to gain insight into how LFS can be more accessible to and beneficial for people of all socioeconomic classes. Paradoxically, however, the current exclusivity of many LFS—whether caused by cost or cultural barriers to entrance—often contributes to the decline of certain, established LFS.

Certain resounding paradoxes of how to develop accessible LFS were revealed to me during an interview yesterday with Mr. Hiroshi Toyoshima, from ‘PR and Social Movement Section’ of Daichi wo Mamoru Kai. Daichi wo Mamoru Kai, or Daichi, is one of Japan’s oldest, most well-established, and largest online organic food delivery systems. When I encountered Daichi’s stand at the farmers’ market last week, I had little idea how relevant the company’s development is to my research on post-WWII Japanese LFS development.

Daichi emerged from the same backdrop of food safety crises that spurred the development of Teikei, Japan’s system of direct producer-consumer distribution, and other consumer cooperatives in the early 1970s. However, Daichi’s origin can be traced more specifically to the failure of the ‘Student Movement’ in the late 1960s. The Japanese Student Movement, which opposed topics ranging from the Anpo treaty to the Vietnam War, failed to gain significant regard and response from the Japanese government.

Mr. Fujimoto, Daichi’s founder, was a prominent student activist, and he was quite disappointed when the Student Movement fizzled out. So, even as Mr. Fujimoto joined his student counterparts in finding work elsewhere, he sought to find an alternative way to make positive social change. At his new job at a publishing company, Mr. Fujimoto learned about what he found to be a peculiar phenomenon: how Japanese farmers used many chemicals to make “the perfect” fruits and vegetables to sell to the market but at the same time produced organic varieties of the same crops to consume themselves. Mr. Fujimoto also recognized the country’s rising fears about food safety, and he sought utilize his newfound knowledge to help make the country’s food supply safer.

Daichi was first established as a pro-organic NGO. The organization’s initial goals were two-fold: one, to get more farmers to produce using organic methods and two, to find customers for those farmers. Two years after its establishment, Daichi’s leaders realized the expansive resources needed to conduct their proposed work. They quit their jobs, and in 1977, transitioned Daichi from an NGO to a for-profit enterprise.

At this point, many Teikei members criticized Daichi for advocating organic food sales over the anti-capitalist ideals of “mutual assistance,” which are outlined in the Teikei Principles. During the 1970s, Daichi also tried marketing its organic food to agricultural cooperatives, yet the cooperatives rejected Daichi’s market structure for their established, barter-like systems. (These same agricultural cooperatives started purchasing organic food from similar market sources 5-to-10 years later.)

Despite criticism by other pro-local and pro-organic Japanese food distribution schemes, Daichi’s goal has always been to increase the sustainability of organic farming in Japan. Since the company’s inception, Mr. Fujimoto has recognized the importance of providing a fair, secure income to organic farmers to ensure that those farmers can continue to produce organic crops in the upcoming years.

Through the late 1980s, Daichi did this by providing an established group buying structure through which consumers could gain easy access to environmentally and socially sustainable food sources. In the late 80s, Daichi made its business more accessible and simple for consumers by transitioning to an individual ordering system.

While Daichi doesn’t require its producers to be certified organic, they must adhere to Daichi’s own rigorous production standards, which incorporate many organic principles. Furthermore, a key part of Daichi’s business activities are its social activities, which have ranged from organizing anti-GMO protests to hosting educational farm trips for school groups.

Today, Daichi operates primarily through its website. It connects its 300,000 customers to 2,500 producers, and the company maintains close relationships with each of those producers. Despite Daichi’s successes, however, the company has struggled to maintain its long-term sustainability. It has had difficulty attracting new customers, and the majority of its current customer base are in the 40s or older. Mr. Toyoshima attributes Daichi’s inability to attract young consumers to young people’s “inability to read sentences very carefully.” He cites young people’s busy lives, economic constraints, and familiarity with small screens and catchy advertisements as why they don’t choose to order food from Daichi instead of other online retailers, which tend to be less expensive and sell a only a small percentage of organic food.

Perhaps some of Daichi’s troubles will be answered this fall, when it merges with Oisix, another online food retailer. Unlike Daichi, Oisix currently maintains a younger consumer base. Oisix doesn’t have as rigorous of quality standards as Daichi, and the food items it sells are generally less expensive than their Daichi counterparts. However, Mr. Toyoshima described to me Daichi’s and Oisix’s current combined efforts, through which Daichi has started selling some of its products through Oisix’s online platform, and many customers are beginning to choose the higher quality, more expensive (Daichi) products over the Oisix ones.

Mr. Toyoshima has high hopes for the upcoming Daichi-Oisix merger, yet Daichi still faces much uncertainty ahead. Mr. Toyoshima is particularly anxious about the Daichi’s transition from a private to public company: he fears that the new shareholders will inhibit Daichi’s engagement in CSR activities and restrict the company to more mainstream market activities. Sure, it’s been ten years since Daichi’s last anti-GMO protest, yet the upcoming merger may make it harder to Daichi to prioritize any sort of oscial activities.

Finally, the paradox I mentioned about 850 words ago (sorry, these posts are long, I know):

Based on Mr. Fujimata’s and Daichi’s principles, the best way to secure a sustainable local food system—one based on the principles of organic farming—is to ensure organic farmers’ income and livelihoods to ensure they will continue to produce organic products. To continue ensuring organic farmers’ incomes, Daichi must increase its consumer base. To do that, Daichi tries to make more Japanese people interested in buying organic products: It does this through educational activities as well as providing an easy outlet (online shop) for customers to purchase organic products. However, past a certain threshold, Daichi cannot recruit anymore consumers who are really dedicated to purchasing organic food over less expensive food. Daichi then has to resort to cost-cutting techniques to attract new, cost-conscious customers. To make costs lower, however, Daichi has to sacrifice some of its quality standards or profit margin to farmers, both which reduces the company’s contributions to Japan’s food security.

~ Paradox 1 ~

More Daichi customers –> increased Japanese food security

But Daichi’s only potential customers left are those who value immediate cost-savings over organic principles

To recruit those customers, Daichi has to lower its organic standards and potentially risk decreasing its company’s contributions to increasing Japanese food security

After two weeks in Japan, I’ve experienced another significant revelation in terms of my personal opinions of food security. Before I began this trip, I was highly skeptical of whether local food systems can (I highly recommend the book The Locavore’s Dilemma) ensure a country’s food security any better—or even to the same extent—that secured, diversified international food trade networks can. Yet, throughout the course of my research here, I’ve encountered substantial anxiety from a wide range of interviewees about the rising prices of imported foods. Sure, Japan’s imported food supply may be secure to the extent that the country does not face any impending trade barriers due to global conflict. In fact, my first week in Tokyo, Japan and the EU began the new Free Trade Agreement. Furthermore, Japanese government officials currently seek to revive the Trans-Pacific Partnership (even without the U.S.).

Yet strolling down the produces aisles of Japanese supermarkets, I understand why my interviewees are concerned. Yes, the $100, gorgeous packages of gift-wrapped, flawless fruits are something particular to Japanese people’s values of perfection. Yet the prices of more practical commodities, such as butter, sugar, wheat, and meat, are also increasing significantly. These price increases, which can be attributed to rising global fuel prices, increased demand from neighboring countries, like China, and climate-caused lower crop yields internationally, due pose a significant threat to Tokyo’s food security.

And, another paradox: when the economy is not doing well, Japan’s food security declines. Furthermore, increasing Japanese, domestic agricultural production can increase Japan’s food security, especially during rough economic times, by making the country less dependent on imported food with volatile prices. However, as Daichi has experienced, it is very costly to increase Japanese domestic production, and so that might not be possible during economic downturns—when food insecurity is the biggest issue.

~ Paradox 2 ~

Bad economy –> Japanese can’t afford high prices of imported food; food security declines

Increased Japanese, domestic agricultural production –> less expensive food in Japanese markets; food security increases

Bad economy –> too difficult/costly to increase Japanese domestic agricultural production

And with all that, I’m heading out of Japan tomorrow. I’ll arrive in Singapore tomorrow night, where I’m excited to learn from local food proponents in a country that imports over 90 percent of its food supply… yet that is known as the second most food secure nation in the world.

SYEDA GHULAM FATIMA

When I met Fatima for the first time, she struck off as a lovely, graceful lady. At the same time, she managed to command respect from everyone at the Bonded Labour Liberation Front. Now, those are a few signs of a great leader.

Fatima was very comfortable in front of the camera too. I did an RTVF Documentary class with Debra Tolchinsky and found out how hard it is to get great cast for a documentary. Fortunately, Fatima knew how to be present in front of a camera. Her awareness of herself subjected to the camera is awesome. When we lacked in our interview with ex-bonded laborers, she would chip in to bring genuine thoughts and emotions from them. She takes her time. She’s very charismatic.

It’s not surprising, especially after all the media coverage that she received after her feature in Humans of New York. That includes her receiving the Clinton Global Citizen Award in 2015.

We had the chance to Skype with a producer from VICE, Fazeelat Aslam, who has worked with Fatima since 2011, for a feature doc, and got to know how much dedication Fatima has for the cause. We found out from her that even after all the travels and threats Fatima faced, Fatima continues to work on the grassroots level more confidently than ever.

The picture above shows a man, from Bahwalpur, south of Pakistan, intimately tells how he managed to leave one of the brick kilns alone without his family. He fears that his family may not think he is alive anymore. Fatima hears these stories every other day. I feel that it takes out-of-this-world dedication to keep fighting this good fight.

Just like any research, things change for the better or worse. We faced a few bumps along the way, considering how delicate access can be for this subject matter and of course, the weather. We have a few surprises too (pictured below).

When Brandon Stanton suggests that Fatima leaves Pakistan and operate BLLF from overseas, she smirked at the idea. She is here to finish what she started.

When plans change

One lesson in research: you can never expect things to go according to plan.

Although last week was in many ways really exciting for me and my lab group, and involved lots of new instruments and new opportunities, we also hit a number of road bumps. The freeze dryer, an essential step in preparing sediment samples for extraction, spent three days forgetting how to vacuum down, and a number of sample vials were broken in the process. The gas chromatograph, the workhorse of lipid analysis, ran a leak overnight and needed two days’ worth of troubleshooting. An unexpected power fail in the building luckily didn’t damage our most important instruments, which have backup power, but it interrupted overnight tests and fried a computer. Every road bump cost me the ability to continue with my primary work that day.

The photos that I posted from this week capture the excitement of scientific research, of using new tools and finding surprises and making progress. It’s easiest to gloss over the tough parts, the times when you do the same thing over and over with no success or spend precious hours babysitting a broken machine. For one thing, this stuff is not nearly as fun to talk about. But road bumps and long days are the reality of research in most settings: there will be progress and excitement, but they’ll always be accompanied by troubleshooting or frustration or mind-numbing lab methods.

It can be hard to keep perspective in the moment, but I do try to remind myself to take the bad with the good. Was this week difficult? Yes, but given the circumstances, I was lucky to make as much progress as I did. Did things go according to plan? No, but I am lucky to have two wonderful, bright, inspiring advisors and a number of fantastic coworkers who are here to help. Broken vials are all part of the process.

Week Five!

My first full week back after the fourth of July felt like a long one! Fortunately, this was just what I needed to get everything with my project finalized to launch next week. I will be collecting data over these next few weeks and then analyzing the results of my interviews and surveys at the end of August.

I spent much of my time this week programming the screening, consent, and survey into Redcap, Northwestern’s online research database. It was a big learning curve for me over these past few months to not only learn how to use the database, but how to write simple code for the surveys and forms I needed to create. I was so proud when at the end of the week my twenty page form was complete and functional with its layers of branching logic. With final approval from Dr. Phillips, it should be participant-ready and we can use it to start recruiting at the beginning of next week!

This was also the first week of the Fit2Thrive intervention, so our study participants were all making progress towards their goal of 30 minutes a week of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity. One of the highlights of the week was serving as an exercise coach to the breast cancer survivors. Half of our participants are scheduled to receive biweekly coaching calls from the study team (that’s me! And my coworkers) where we review their progress and offer suggestions and words of motivation for the coming weeks. I wrote the scripts for these calls back in the spring, and so it is fulfilling to see my work come to fruition. It is heartwarming to take these few brief minutes in the day to check in on our participants individually. I am learning so much about how to motivate others and form long-term relationships with them, and these are skills that will translate well into my practice of medicine one day.

I can’t wait to share more updates with you next week about my first interviews!

SO, WHAT IS BONDED LABOR?

We set out for Lahore to find out why the practice of bonded labor is still happening despite it being illegal in Pakistan. Pre-assumptions aside, we needed to speak with people who understand the topic well. So far, we spoke with those who are in the brick kiln industry, which practices bonded labor widely, a lawyer and an activist.

My capable teammates worked with local fixers to get us in touch with brick kiln owners, whose kilns are on the outskirts of Lahore, Kasur. It was easier to film them than expected because I feel that we were ready to hear their perspective on the topic. Before anything else, let me show you some pictures from our time in the brick kilns.

These laborers do not have access to safety nets that should be provided by the government. It is not surprising that someone else fills that void. That someone else could be anybody. For the sake of our study, they are brick kiln owners. These laborers needed money to start off their lives and turned to these owners. In return? They need to work in the brick kilns.

The laborers often continue to borrow money for their needs. At the same time, due to the loan interest, they are often serving their time in the kilns to pay off the debt owed by their parents or grandparents. That’s why bonded labor is also known as modern-day slavery. I suggest you read this article written by Mehvish Muneera, a lawyer whom we spoke with, to understand the practice through a legal lens.

You can blame the disparity in literacy between brick kiln owners and the laborers. These laborers do not understand the loan agreement that they signed up for. The owners, on the other hand, argue that they provide basic needs like housing and healthcare to these laborers, something the government does not provide.

In March 1992, the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act was passed, hoping to end the “bonded labor system.” However, due to the lack of law enforcement, the absence of a safety net for these laborers and the increasing need for bricks in new residential towns, the practice continues to this day.

Since the human resources of the brick kiln industry work outside of the law, there is plenty of room for further exploitation. While the lack of law enforcement is apparent, someone else takes the matter into her own hands.

You may have seen her from Humans of New York. Her name is Syeda Ghulam Fatima.

Core sampling week, in pictures

As compared to usual, lots happened this week! Here’s a summary of what’s been happening, told in pictures.

Testing out our brand-new core splitter on an empty core tube.

My very own freshly split core!

The new core scanner took super-high-definition photos of my core so that changes in color and texture were easier to see.

Our first chance to test out the new core sampling tools we made out of sheet metal.

Making my way down the core! The larger sample vials will be used for lipid extractions (my main project, and what I talk about all the time), and the smaller tubes will be used to take carbon to nitrogen ratios (which can help us understand whether more terrestrial or more aquatic plants are represented).

This section has shells!!

Shell fragments held up on a spatula.

These samples are ready to freeze dry!

Tokyo: Taiyo Marche & Teikei

Sunday morning, I woke up early to meet Dr. Masashi Tachiwaka at a farmers’ market. Taiyo Marche, or ‘Market of the Sun’ is regarded as Tokyo’s largest farmers’ market. It hosts about 100 producers of fresh foods, prepared foods, crafts, and other goods every other weekend. Dr. Tachiwaka, a sociologist from Nagoya University who specializes in agriculture and food studies, chose to visit the market together despite that he’d never been before. (If there are any budding food systems researchers out there, I would highly recommend visiting a farmers’ market with a researcher who focuses on food systems studies.)

Dr. Tachiwaka and I entered the market together, passed by the large variety of international-themed food trucks, and headed to the information stand. We learned together that the four-year-old market was created and is managed by Mitsui, which per Wikipedia “is one of the largest sogo shosha in Japan… Its business area covers energy, machinery, chemicals, food, textile, logistics, finance, and more.”

I wasn’t able to determine the exact cost structure of the market—i.e. whether/how much Mitsui pays to rent the public park space or how much vendors pay to rent their own spaces. However, Dr. Tachiwaka deduced that Mitsui must make a significant profit from the market. The market takes place in Kachidoki, a residential neighborhood on a man-made island near Tokyo’s center. The existence of the market makes the neighborhood more lively, increasin its popularity and thus, its rent prices (of the homes and developments that Mitsui owns).

I must confess that I’m an avid visitor of farmers’ markets, and thus, the Taiyo Marche looked quite familiar at first. Indeed, there were a bit more jewelry stand than I might normally expect, the stand of imported wine made me laugh, and I was surprised by how almost every individual fruit and vegetable was wrapped in plastic—just like in all Japanese super markets.[*] Yet beyond these few differences, I strolled the aisles accepting samples like a pro, enjoyeing the brightly colored produce around me, and generally thought I had an idea of this market’s basic form and function.

Soon, however, Dr. Tachiwaka began describing to me how different this market is compared to the majority of Japanese farmers’ markets, and I let my farmers’ market expert hubris go. Dr. Tachiwaka explained how most farmers’ markets in Japan are owned by agricultural cooperatives. They take place in permanent locations, where producers drop off their goods in the morning and pick up whatever is left at the end of the day. Taiyo Marche, along with about ten other Tokyo farmers’ markets, where consumers sell their own goods at stands, is still a largely new concept in Japan. It’s a part of what I’d personally categorize as a new wave of local food systems development.

The first wave of LFS development, then, began in the 1960s, following a few drastic incidents where Japanese industrial activities harmed people’s health. While the Kamioka Mine had released significant quantities of cadmium since the beginning of the 20th century, wartime activities caused the quantity of pollution to significantly increase. The river water, contaminated with cadmium and other heavy metals, was used to irrigate Toyama Prefecture’s rice fields and caused a mass appearance of Itai-Itai disease, or cadmium poisoning. In 1961—almost 50 years after the first case of the disease—the Mitsui Mining and Smelting’s Kamioka Mining Station was finally pinpointed as the source of the cadmium and other heavy metal pollution and the cause of the disease.[†]

In 1956, Chisso Corporation released its industrial wastewater, which contained untreated organic mercury, along the Minimata River. Chisso Co.’s pollution caused Minimata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning. Not only did Japanese people suffer directly from Minimata disease, but the government’s and Chisso Co.’s unsatisfactory responses to the disease prompted growing discontent with and distrust in industry behavior and government policy, which accompanied rising concerns about food safety. In 1965, Showa Denka Co.’s pollution of the Aganogawa River, which caused a second wave of the Minimata Disease, amplified these concerns.

Researchers and conscious consumers with whom I’ve discussed topics of food safety in Japan have rattled off lists of how Japanese industry and industrial agriculture (not to mention non-Japanese agriculture) have harmed Japanese people’s health for over the last half-century: e.g. factory smoke in Yokkaichi City and Kawasaki City have caused unprecedented rates of asthma, food additives used in the 1960s contaminated breast milk and caused infant deaths, fake “organic” and “no chemical” labels have deceived consumers about the safety of their food, pesticides continuously harm humans’ health, and Fukushima contaminated food supplies….

After WWII, Japan underwent massive economic and industrial growth. By 1970, the GNP was rising by 10 percent a year. The Japan Organic Agriculture Association (JOAA) was established in response to how “hasty industrialization brought about environment contamination and destruction” (Japan Organic Agriculture Association, 1993, p. 1).[‡] The JOAA, established in 1971, is an independent, non-profit organization comprised mostly of producers and consumers who seek to expand organic agriculture in Japan. It is funded exclusively by membership fees and thus remains independent of any government or corporate affiliations. At the time of its founding, the JOAA recognized a number of serious problems with “modern agriculture” in Japan: a declining number of farmers, increasing age of farmers, and decline of the amount of farmland; soil degradation due to large-scale successive monoculture and loss of humus; a rise in plant diseases and pests caused by a loss of a natural ecological balance; agriculture-caused chemical contamination of human bodies, agricultural produce, soil, and water; and a declining food self-sufficiency rate and am increasing quantity of imported livestock feed.

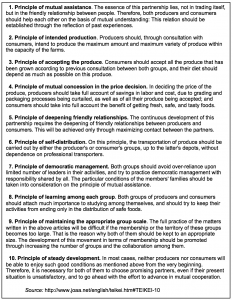

To combat these problems, the JOAA established the “teikei” system, a direct distribution system between producers and consumers. Yet JOAA literature emphasizes how describing Teikei as just a way of selling or distributing farm produce to consumers does not do Teikei justice. Teikei “is not in a true sense of the meaning a transaction of merchandise. Rather, it is an amicable interactive relationship between people. The underlying philosophy is not that of competition but of coexistence and symbiosis based on mutual support, the spirt of cooperation… Teikei is a holistic system…a comprehensive cultural activity that gives self-reliance to farmers and a new life culture to consumers. ” (JOAA, p. 5-6, 2010.) Furthermore, Ichiraku Tero, a preeminent philosopher and the creator of the Ten Principles of Teikei also preached self-reliance and mutual support based on independence and autonomy of the individual. Today, Teikei is still best defined by its ten founding principles:

One important clarification is the difference between the significance of ‘organic’ in JOAA’s name and in Japanese food policy/broader food discourse. The JOAA’s principles of organic, and how they manifest in Teikei, span far beyond the. The Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestsry, and Fishery’s “Specified JAS [Organic] Standard.” In fact, JOAA has taken a public stance against to the JAS standard. JOAA members disagree with the JAS’s vague delineations of what makes something organic, such as production “with a reduced amount of chemicals” and “products with a small amount of chemicals.” JOAA members also perceive that and disagree with how the government’s certification program is greatly influenced by the demand of profit-seeking organizations (JOAA, p. 6, 1993).

In contrast to the inadequate government organic standards, a report published by the JOAA in 2010 describes Teikei as “a new relationship that can save humanity and nature and is a quiet revolution to build an everlasting stable society in place of the capitalist economy” (Michio, p. 7, 2010). The report describes how “through this humble but strong movement, we have developed the sustainability of food, making it possible to secure a livelihood for both producers and consumers. Teikei has become the driving force for organic agriculture based on rural nature and culture” (JOAA Committee for Organic Agriculture Production, p. 5, 2010). Yet, while Teikei might have increased the sustainability of food production practices in Japan, is the movement sustainable itself?

Dr. Hiroko Kubota, a consumer movement researcher in the Faculty of Economics at Kokugakuin University is skeptical whether Teikei will persist alongside the aging of its original members, shift in Japanese consumer preferences, and urban residents’ increasingly busy urban lifestyles. Dr. Kubota, a member of three Teikei groups herself, has observed Teikei membership and the number of Teikei groups significantly decline in the past decade. Despite that young Japanese people didn’t personally experience the numerous food safety crises that motivated the founding of Taikei and caused many initial members to join Teikei, Dr. Kubota described how younger Japanese generations still are quite concerned about food safety. However, Dr. Kubota clearly stated, “young people don’t want to join a movement”—whether they’re too busy with work, their smartphones, or whatever— “so we have to create another kind of system to support small farmers.” Rather than expand their extra time resources to participation in a participant-led Teikei group, young people in Tokyo are increasingly turning to other markets to buy organic and local food, such as farm shops, farmers’ markets, and online food delivery services.

And so, back to the Taiyo Marche farmers’ market. As we wandered through the farmers’ market aisles, Dr. Tachiwaka pointed out to me one “organic” stand. We stopped to talk to the producers, and as I learned a bit more, I was surprised to find that this stand wasn’t in fact run by any single organic farmer or even any organic agricultural cooperative. Rather, it was run by Daichi, one of the largest web-based agricultural delivery services in Japan.

I’m meeting with a member of Daichi’s Corporate Social Responsibility Department next week, so I’ll hold off on too much detail about the company for now. However, some that I’ve learned through some preliminary emails (and of course, Google Translating the company’s webpage)… Daichi wo Mamoru kai, or Daichi, delivers (organic) produce, dry goods, meats, eggs, fish/seafood, dairy, among other items all over Japan. The company was established in 1977, following its prior establishment as a pro-organic NGO a few years earlier. Today, the company’s mission is to promote domestic agricultural industries, and the company’s leaders are highly motivated by Japan’s low food self-sufficiency rate. Daichi’s customers are primarily well-educated, well-off financially, and in their 40s or over. However Daichi will soon merge with Oisix, a similar company with a younger consumer base. Both of these companies currently answer Japanese market demand for reliable, high-quality, organic, domestic food products, which urban residents can obtain without the need to devote excessive time resources to obtain—although they may end up spending a bit more money.

Before we left the Daichi stand at the farmers’ market, one of the workers gave me a packet of kale—three long kale leaves in a plastic bag. He said something about the holes on the kale caused by a caterpillar. While I wasn’t sure if the caterpillar holes meant why he didn’t care about giving up the kale—whether he wasn’t allowed to sell it or if people just weren’t likely to buy that bag of kale—I graciously accepted my ~27th fresh food item given to me since I’ve been in Tokyo.

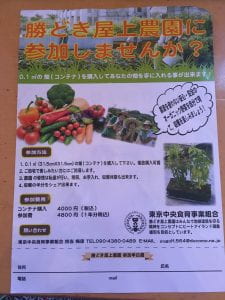

Another stand I was pleasantly surprised by at the farmers’ market was run by the producer located closest to the market—just on a nearby rooftop! The farmers’ market stand serves a dual purpose for the community farm: It’s an outlet for the farm to sell excess vegetables, and it’s also a way for the community farm owner to advertise his farm. The owner of the rooftop farm, Mr. Umehara, was motivated to create the farm for environmental reasons: to help mitigate the heat island effect. Yet today, he thinks the greatest benefit are how many people are involved and benefit from the community farm. There are currently ten families who work on the farm. They each farm their own plots and share the harvest. One family also owns a restaurant, and they incorporate the crops they produce on the farm into their dishes at the restaurant. The plot rental fee is not insignificant, yet it is less than that of other rooftop, community or allotment farms in Tokyo–likely given that Mr. Umehara’s friend owns the building, so he does not have to pay rent.

Given the apparent prosperity of Tokyo and the surrounding regions I’ve visited, it’s difficult to fathom Japan’s high poverty rate. A 2015 survey by Japan’s Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry found that 1 in every 7 children were from families living on less than half of the national median household disposable income. Like the local food systems I have studied in other countries, prominent local food systems I’m studying in Tokyo can be exclusionary due to potential consumers required financial and time resources. The intense time resources required to participate in Teikei have caused younger generations to prefer to purchase organic, local food from online delivery services instead of self-organized producer-consumer networks. And while organic online shops might sell at higher prices than the produce found in supermarkets, the time young people save by not visiting the supermarket makes the price increase of online shopping relatively insignificant. Furthermore, other online delivery services, like Seiyu and Co-op, actually sell domestic (organic and not organic) food at lower prices than supermarkets. The rising popularity of online food shopping is likely to have great implications for the further development of local food systems in Japan, and in their accessibility to difference socioeconomic groups of people.

Meanwhile, the cost of renting plots at urban farms in Tokyo remains prohibitively expensive for the majority of Tokyo residents. While this is not the case in other cities and regions throughout Japan, I wonder what the cost-barriers of agrileisure means for Tokyo residents’ physical engagement in food production. Can kitchen and terrace gardens provide people with the same fulfilling connection to food production that shared farming spaces can? What are the different benefits and challenges of individually-developed, private (micro?…) local food systems versus community-based local food systems?

Finally, if you’ve made it to the end of this blog post, thanks for following my 17 different tangents of thought! I’m currently in practice to tie together one research trip to 7 countries studying ~15 different types of local food systems into one final report. And in the meantime, I still have about 25 types of food to try in Tokyo.

Sources:

Japan Organic Agriculture Association. (1993). ‘TEIKEI’ system of Japanese Organic Agriculture Movement: Country Report for the First IFOAM Asian Conference.

Japan Organic Agriculture Association, Committee for Organic Agriculture Promotion (2010, Oct). Teikei Networks for Forests, Homelands and the Seas – All Connected Through Humus: River Basin Region Self Sufficiency and Teikei will Drive Organic Agriculture.

[*] This is a key hint to Japanese citizens’ concerns about food safety, and more on that later!

[†] Yes, this is the same Mistui company that created the farmers’ market I visited today.

What’s in a Name? Redemption.

So far my days have blended together like the colors I mix to paint with: wake up, paint while listening to music, cook, paint again, and when my recommended hours are over (or I’m just too tired to continue) I watch TV. I did a check in today with my adviser, which went well, and I finally finished the first two paintings, Blue and Apple. I decided to celebrate with a nap and some funyuns, and then I prepped the next two canvasses: The and Why.

I was shocked when I finished the two paintings. It’s been a minute since I actually felt something was well and truly finished. It’s a blissful, surreal feeling, like the end of a 5k.

Alec put me in a bit of a worry last night. I had started texturizing the ‘p’s in apple, and I was worried I was too off the mark. But oil paint takes forever to dry, so I figured if it wasn’t accurate I could just scrape and go again. But the labor involved in that one letter was tremendous. I had an inspo picture for lichen, which Alec described as being the texture/mottling effect of the color, so I sat in front of that single letter adding paint for an hour to get the desired effect I wanted. I had to continually shape the wax I was working with to get the right texture. Plus, nature is very precise. To mimic nature, you have to understand the rules it operates by, and create accordingly. He didn’t get back to me until this morning, impressed with my accuracy, but by then I had figured he had already seen it and okayed it. He’s good like that. But still…I was worried. It’s not like I’m representing what I see here. I’m a conduit, like wire, between the canvas and his brain.

And then, out of my Instagram post, came a miracle. My friend Ally, trusted ally and bestie, has synesthesia. Her words are colored. Bless. Just as I was looking for someone else to do this work for, she popped her head into my inbox, asking which colors I was gonna use, and how they probably weren’t going to be her colors, and in between my queries and qualifiers, unprompted, she tells me she also sees my name in pretty colors.

Both she and Alec give me new reasons to love my name. Growing up, I was always made fun of, called Kimono, kimano, kimiko, etc.. Literally anything a kid about 12 and under could think of to demean a name they’d never heard of before. But now, as a young adult, what I used to get made fun of for makes me cool. My name is different. Therefore, I must be somehow different (read: cooler and more refreshing) than the names and people someone is normally used to. I’m an unknown. But with Ally and Alec my name is more than just exotic sounding. lt comes to life for them in a way that it never did for me. Alec see my name as this crossfade between sunset, night, and the daytime (hell, it’s the banner for this blog). And Ally sees my name as this pinkish/purple and white confection. So for the first time in my life, my name is not just weird, it’s beautiful, and I owe that to the involuntary neurological reactions that my friends’ brains have to my name. Weird? Yeah, probably. So what?

People used to say my name was this. What does my name mean for you? Hell, what does your name mean for you?

Do you know what’s in a name?

IN PICTURES – EAT-ULFITRI: SINGAPORE VS. PAKISTAN

Before writing about the pressing issue of bonded labor, let me dedicate this post to one of the most festive times for Muslims: Eidulfitri. After a month of fasting during Ramadhan, we celebrate by performing a mass prayer in the morning and get together with our family and friends after that. We would catch up with each other and eat, a lot. That’s for my family, at least.

I arrived in Lahore, Pakistan, a little less than a month ago. I had the privilege of spending the second week celebrating Eid with Ammar’s family and taking some photos of my experience. Lucky for me, my sister, back home in Singapore, enjoys taking photos too. I thought I could use this post to show you some similarities I learned between the Eid celebration in Singapore and Pakistan through our photos.

1) A Hungry Guest Is an Angry Guest

Nothing says Eid like eating like you have fasted for a whole month. Just like in Singapore, in a typical Pakistani household, the morning of Eid is spent cooking for the countless incoming guests.

Singapore

Pakistan

2) Traditional Clothes Are the Best

Eid fashion is the best. During this time of the year, my family will flaunt the traditional Malay dresses, like baju kurung and kebaya to name a few. Just as back home, the traditional clothes here in Pakistan, shalwar kameez and kurta, are just as beautiful.

Singapore

Pakistan

3) Kids Are Photogenic

Who doesn’t like photos of kids? In traditional clothes? What?!

Singapore

Pakistan

4) Proud of Our Matriarch

My grandmother plays a pivotal role in the family. She brings the family together. Everyone hopes to get her blessings in whatever we intend to pursue. My time with Ammar’s family in Pakistan confirms that his grandmother has a similar role too.

Singapore

Pakistan

5) Family. Keluarga. Khandaan.

After all, Eid is about getting our families together, be it in Singapore or Pakistan. Let’s end this post with some family portraits.

Singapore

Three generations of inspiring women: mother, grandmother, and sister (left to right) Credit: Nur Munawarah

Pakistan

Commence Phase Two

Tomorrow is the big day…the day we’ve all been waiting for…the day we split the sediment core!

If you’ve read your way through my blog, you’ll know that right now, the core looks like this:

The core was sampled from the bottom of Little Sugarloaf Lake in the summer of 2015, and ever since it was shipped from Greenland to the Axford lab on campus, it’s lived in its coring tube in a huge walk-in freezer. Looking through the plastic, there’s very little we can learn about the core. Basically, we know that the dark brown color indicates a lot of organic material, and that’s about it.

But tomorrow, we’ll split the cylindrical core in half (to give us two half-moon shaped slices of sediment), allowing us to see what’s inside and look at it in two ways. First, we’ll give it a good old-fashioned visual inspection. Are there any places where the color changes? What about the texture? Are the changes stark, or gradual? We’ll also look to find anything we could send out for radiocarbon dating (especially animals’ shells) to get some boundaries on the age of the core.

The more exciting way of looking at the core will be to use the Axford lab’s brand new very shiny Geotek core scanner (installed in the lab today!!). It looks a lot like this…

…and, for scale, I don’t think it would fit in my bedroom! This magnificent metal giant can do just about any analysis anyone would think about doing on an intact core. It takes incredible high definition photos, converts colors to numerical data to more precisely identify color changes, scans for the abundances of numerous elements, and tests for magnetism, among multiple other functions. Gathering all this information will only take a couple hours at most, and it’ll help me get a fuller picture of what the core contains. I’ll be keeping in mind what I learn when I start to explore the biomarkers that are preserved in the sediment, and try to interpret what they mean.

Splitting and scanning the core will start the ramp up top what I’m calling Phase Two (does that give it a top-secret very-important-science vibe?). Phase One, which is starting to wrap up, was the process of extracting, chemically separating, and analyzing the plant samples. I’m very close to having a complete set of data about the plants’ lipid chain lengths and their isotope ratios, so in not too long I’ll be able to analyze and interpret these data, looking for how different groups of plants may have different chemical signatures. But Phase Two is where I’ll get the opportunity to look into the past, traveling back in time as I extract sediment from deeper and deeper in the core (i.e., deeper and deeper layers of mud from the bottom of Little Sugarloaf Lake). Stay tuned for when the time travel begins!