Sunday morning, I woke up early to meet Dr. Masashi Tachiwaka at a farmers’ market. Taiyo Marche, or ‘Market of the Sun’ is regarded as Tokyo’s largest farmers’ market. It hosts about 100 producers of fresh foods, prepared foods, crafts, and other goods every other weekend. Dr. Tachiwaka, a sociologist from Nagoya University who specializes in agriculture and food studies, chose to visit the market together despite that he’d never been before. (If there are any budding food systems researchers out there, I would highly recommend visiting a farmers’ market with a researcher who focuses on food systems studies.)

Dr. Tachiwaka and I entered the market together, passed by the large variety of international-themed food trucks, and headed to the information stand. We learned together that the four-year-old market was created and is managed by Mitsui, which per Wikipedia “is one of the largest sogo shosha in Japan… Its business area covers energy, machinery, chemicals, food, textile, logistics, finance, and more.”

I wasn’t able to determine the exact cost structure of the market—i.e. whether/how much Mitsui pays to rent the public park space or how much vendors pay to rent their own spaces. However, Dr. Tachiwaka deduced that Mitsui must make a significant profit from the market. The market takes place in Kachidoki, a residential neighborhood on a man-made island near Tokyo’s center. The existence of the market makes the neighborhood more lively, increasin its popularity and thus, its rent prices (of the homes and developments that Mitsui owns).

I must confess that I’m an avid visitor of farmers’ markets, and thus, the Taiyo Marche looked quite familiar at first. Indeed, there were a bit more jewelry stand than I might normally expect, the stand of imported wine made me laugh, and I was surprised by how almost every individual fruit and vegetable was wrapped in plastic—just like in all Japanese super markets.[*] Yet beyond these few differences, I strolled the aisles accepting samples like a pro, enjoyeing the brightly colored produce around me, and generally thought I had an idea of this market’s basic form and function.

Soon, however, Dr. Tachiwaka began describing to me how different this market is compared to the majority of Japanese farmers’ markets, and I let my farmers’ market expert hubris go. Dr. Tachiwaka explained how most farmers’ markets in Japan are owned by agricultural cooperatives. They take place in permanent locations, where producers drop off their goods in the morning and pick up whatever is left at the end of the day. Taiyo Marche, along with about ten other Tokyo farmers’ markets, where consumers sell their own goods at stands, is still a largely new concept in Japan. It’s a part of what I’d personally categorize as a new wave of local food systems development.

The first wave of LFS development, then, began in the 1960s, following a few drastic incidents where Japanese industrial activities harmed people’s health. While the Kamioka Mine had released significant quantities of cadmium since the beginning of the 20th century, wartime activities caused the quantity of pollution to significantly increase. The river water, contaminated with cadmium and other heavy metals, was used to irrigate Toyama Prefecture’s rice fields and caused a mass appearance of Itai-Itai disease, or cadmium poisoning. In 1961—almost 50 years after the first case of the disease—the Mitsui Mining and Smelting’s Kamioka Mining Station was finally pinpointed as the source of the cadmium and other heavy metal pollution and the cause of the disease.[†]

In 1956, Chisso Corporation released its industrial wastewater, which contained untreated organic mercury, along the Minimata River. Chisso Co.’s pollution caused Minimata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning. Not only did Japanese people suffer directly from Minimata disease, but the government’s and Chisso Co.’s unsatisfactory responses to the disease prompted growing discontent with and distrust in industry behavior and government policy, which accompanied rising concerns about food safety. In 1965, Showa Denka Co.’s pollution of the Aganogawa River, which caused a second wave of the Minimata Disease, amplified these concerns.

Researchers and conscious consumers with whom I’ve discussed topics of food safety in Japan have rattled off lists of how Japanese industry and industrial agriculture (not to mention non-Japanese agriculture) have harmed Japanese people’s health for over the last half-century: e.g. factory smoke in Yokkaichi City and Kawasaki City have caused unprecedented rates of asthma, food additives used in the 1960s contaminated breast milk and caused infant deaths, fake “organic” and “no chemical” labels have deceived consumers about the safety of their food, pesticides continuously harm humans’ health, and Fukushima contaminated food supplies….

After WWII, Japan underwent massive economic and industrial growth. By 1970, the GNP was rising by 10 percent a year. The Japan Organic Agriculture Association (JOAA) was established in response to how “hasty industrialization brought about environment contamination and destruction” (Japan Organic Agriculture Association, 1993, p. 1).[‡] The JOAA, established in 1971, is an independent, non-profit organization comprised mostly of producers and consumers who seek to expand organic agriculture in Japan. It is funded exclusively by membership fees and thus remains independent of any government or corporate affiliations. At the time of its founding, the JOAA recognized a number of serious problems with “modern agriculture” in Japan: a declining number of farmers, increasing age of farmers, and decline of the amount of farmland; soil degradation due to large-scale successive monoculture and loss of humus; a rise in plant diseases and pests caused by a loss of a natural ecological balance; agriculture-caused chemical contamination of human bodies, agricultural produce, soil, and water; and a declining food self-sufficiency rate and am increasing quantity of imported livestock feed.

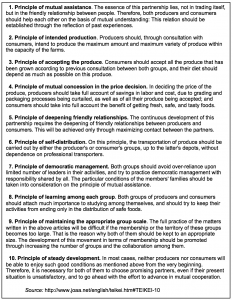

To combat these problems, the JOAA established the “teikei” system, a direct distribution system between producers and consumers. Yet JOAA literature emphasizes how describing Teikei as just a way of selling or distributing farm produce to consumers does not do Teikei justice. Teikei “is not in a true sense of the meaning a transaction of merchandise. Rather, it is an amicable interactive relationship between people. The underlying philosophy is not that of competition but of coexistence and symbiosis based on mutual support, the spirt of cooperation… Teikei is a holistic system…a comprehensive cultural activity that gives self-reliance to farmers and a new life culture to consumers. ” (JOAA, p. 5-6, 2010.) Furthermore, Ichiraku Tero, a preeminent philosopher and the creator of the Ten Principles of Teikei also preached self-reliance and mutual support based on independence and autonomy of the individual. Today, Teikei is still best defined by its ten founding principles:

One important clarification is the difference between the significance of ‘organic’ in JOAA’s name and in Japanese food policy/broader food discourse. The JOAA’s principles of organic, and how they manifest in Teikei, span far beyond the. The Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestsry, and Fishery’s “Specified JAS [Organic] Standard.” In fact, JOAA has taken a public stance against to the JAS standard. JOAA members disagree with the JAS’s vague delineations of what makes something organic, such as production “with a reduced amount of chemicals” and “products with a small amount of chemicals.” JOAA members also perceive that and disagree with how the government’s certification program is greatly influenced by the demand of profit-seeking organizations (JOAA, p. 6, 1993).

In contrast to the inadequate government organic standards, a report published by the JOAA in 2010 describes Teikei as “a new relationship that can save humanity and nature and is a quiet revolution to build an everlasting stable society in place of the capitalist economy” (Michio, p. 7, 2010). The report describes how “through this humble but strong movement, we have developed the sustainability of food, making it possible to secure a livelihood for both producers and consumers. Teikei has become the driving force for organic agriculture based on rural nature and culture” (JOAA Committee for Organic Agriculture Production, p. 5, 2010). Yet, while Teikei might have increased the sustainability of food production practices in Japan, is the movement sustainable itself?

Dr. Hiroko Kubota, a consumer movement researcher in the Faculty of Economics at Kokugakuin University is skeptical whether Teikei will persist alongside the aging of its original members, shift in Japanese consumer preferences, and urban residents’ increasingly busy urban lifestyles. Dr. Kubota, a member of three Teikei groups herself, has observed Teikei membership and the number of Teikei groups significantly decline in the past decade. Despite that young Japanese people didn’t personally experience the numerous food safety crises that motivated the founding of Taikei and caused many initial members to join Teikei, Dr. Kubota described how younger Japanese generations still are quite concerned about food safety. However, Dr. Kubota clearly stated, “young people don’t want to join a movement”—whether they’re too busy with work, their smartphones, or whatever— “so we have to create another kind of system to support small farmers.” Rather than expand their extra time resources to participation in a participant-led Teikei group, young people in Tokyo are increasingly turning to other markets to buy organic and local food, such as farm shops, farmers’ markets, and online food delivery services.

And so, back to the Taiyo Marche farmers’ market. As we wandered through the farmers’ market aisles, Dr. Tachiwaka pointed out to me one “organic” stand. We stopped to talk to the producers, and as I learned a bit more, I was surprised to find that this stand wasn’t in fact run by any single organic farmer or even any organic agricultural cooperative. Rather, it was run by Daichi, one of the largest web-based agricultural delivery services in Japan.

I’m meeting with a member of Daichi’s Corporate Social Responsibility Department next week, so I’ll hold off on too much detail about the company for now. However, some that I’ve learned through some preliminary emails (and of course, Google Translating the company’s webpage)… Daichi wo Mamoru kai, or Daichi, delivers (organic) produce, dry goods, meats, eggs, fish/seafood, dairy, among other items all over Japan. The company was established in 1977, following its prior establishment as a pro-organic NGO a few years earlier. Today, the company’s mission is to promote domestic agricultural industries, and the company’s leaders are highly motivated by Japan’s low food self-sufficiency rate. Daichi’s customers are primarily well-educated, well-off financially, and in their 40s or over. However Daichi will soon merge with Oisix, a similar company with a younger consumer base. Both of these companies currently answer Japanese market demand for reliable, high-quality, organic, domestic food products, which urban residents can obtain without the need to devote excessive time resources to obtain—although they may end up spending a bit more money.

Before we left the Daichi stand at the farmers’ market, one of the workers gave me a packet of kale—three long kale leaves in a plastic bag. He said something about the holes on the kale caused by a caterpillar. While I wasn’t sure if the caterpillar holes meant why he didn’t care about giving up the kale—whether he wasn’t allowed to sell it or if people just weren’t likely to buy that bag of kale—I graciously accepted my ~27th fresh food item given to me since I’ve been in Tokyo.

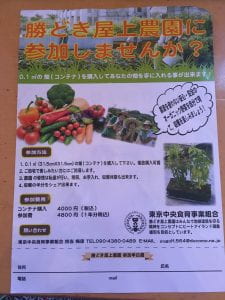

Another stand I was pleasantly surprised by at the farmers’ market was run by the producer located closest to the market—just on a nearby rooftop! The farmers’ market stand serves a dual purpose for the community farm: It’s an outlet for the farm to sell excess vegetables, and it’s also a way for the community farm owner to advertise his farm. The owner of the rooftop farm, Mr. Umehara, was motivated to create the farm for environmental reasons: to help mitigate the heat island effect. Yet today, he thinks the greatest benefit are how many people are involved and benefit from the community farm. There are currently ten families who work on the farm. They each farm their own plots and share the harvest. One family also owns a restaurant, and they incorporate the crops they produce on the farm into their dishes at the restaurant. The plot rental fee is not insignificant, yet it is less than that of other rooftop, community or allotment farms in Tokyo–likely given that Mr. Umehara’s friend owns the building, so he does not have to pay rent.

Given the apparent prosperity of Tokyo and the surrounding regions I’ve visited, it’s difficult to fathom Japan’s high poverty rate. A 2015 survey by Japan’s Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry found that 1 in every 7 children were from families living on less than half of the national median household disposable income. Like the local food systems I have studied in other countries, prominent local food systems I’m studying in Tokyo can be exclusionary due to potential consumers required financial and time resources. The intense time resources required to participate in Teikei have caused younger generations to prefer to purchase organic, local food from online delivery services instead of self-organized producer-consumer networks. And while organic online shops might sell at higher prices than the produce found in supermarkets, the time young people save by not visiting the supermarket makes the price increase of online shopping relatively insignificant. Furthermore, other online delivery services, like Seiyu and Co-op, actually sell domestic (organic and not organic) food at lower prices than supermarkets. The rising popularity of online food shopping is likely to have great implications for the further development of local food systems in Japan, and in their accessibility to difference socioeconomic groups of people.

Meanwhile, the cost of renting plots at urban farms in Tokyo remains prohibitively expensive for the majority of Tokyo residents. While this is not the case in other cities and regions throughout Japan, I wonder what the cost-barriers of agrileisure means for Tokyo residents’ physical engagement in food production. Can kitchen and terrace gardens provide people with the same fulfilling connection to food production that shared farming spaces can? What are the different benefits and challenges of individually-developed, private (micro?…) local food systems versus community-based local food systems?

Finally, if you’ve made it to the end of this blog post, thanks for following my 17 different tangents of thought! I’m currently in practice to tie together one research trip to 7 countries studying ~15 different types of local food systems into one final report. And in the meantime, I still have about 25 types of food to try in Tokyo.

Sources:

Japan Organic Agriculture Association. (1993). ‘TEIKEI’ system of Japanese Organic Agriculture Movement: Country Report for the First IFOAM Asian Conference.

Japan Organic Agriculture Association, Committee for Organic Agriculture Promotion (2010, Oct). Teikei Networks for Forests, Homelands and the Seas – All Connected Through Humus: River Basin Region Self Sufficiency and Teikei will Drive Organic Agriculture.

[*] This is a key hint to Japanese citizens’ concerns about food safety, and more on that later!

[†] Yes, this is the same Mistui company that created the farmers’ market I visited today.