In the middle of November of 2014, I went with the families I was staying with in Mohali and Landra, Punjab, to see Harry Baweja’s animated film Chaar Sahibzaade (tr. Four Sons, Sahibzaade being a formal, respectful term for sons), which tells the story of Guru Gobind Singh’s four martyred sons: the teenage Ajit and Jujhar Singh, who died in battle protecting the Sikh fortress at Anandpur (tr: City of Bliss), and the younger Jorawar and Fateh Singh, who were captured by Sirhind governor Wazir Khan and imprisoned alive in a brick wall because they wouldn’t convert to Islam. These stories are by far the most tragic of Sikh history, as they tell of the sacrifices of children made in defense of the faith. Needless to say, there was not a dry eye in that theater.

This post is a brief departure from the Yuba City Sikh Festival, but I write it as an expansion on the recurring theme of martyrdom in Sikhism. When I return to the festival, I will discuss the Sikh parade and its floats, but the parade cannot fully be understood without first explaining how imagery like that of the chaar sahibzaade shapes and reshapes Sikh memory.

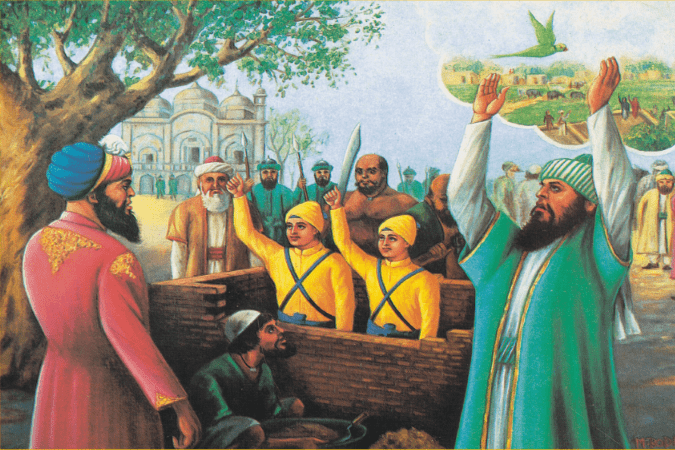

Painting of Jorawar and Fateh Singh chanting the Sikh cry for victory (jakara) as a brick wall is being built around them. From http://www.gurusgangasagar.com. Depending on what source you look at, the sons are 9 and 7, 8 and 6, or 7 and 5, with Jorawar being the elder of the two. Jorawar and Fateh Singh, in all animated depictions I have seen of the two, are shown wearing this exact outfit in these exact colors. Mass reproduction often encodes an image in popular memory until an official film is able to grant it legitimacy.

Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons – particularly the younger two – have been immortalized in Sikh memory because of the gravity of their sacrifice. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib stands in Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, built around the wall in which Jorawar and Fateh Singh were trapped. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib is among the most significant historical gurdwaras in the faith because of the poignancy of the sons’ story, but all historical gurdwaras I have visited in India (roughly twenty for me) stand in memory of a significant event or figure. For example, Gurdwaras Sis Ganj Sahib and Rakab Ganj Sahib in Delhi, and Guru Ka Taal in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, commemorate different stages of the ninth guru’s martyrdom at the hands of Mughal rulers – from his arrest to his execution to the well from which he drank before he died. Gurdwara Keshgarh Sahib in Anandpur Sahib (down the hilltop where Ajit and Jujhar Singh died), birthplace of the Khalsa, displays Guru Gobind Singh’s weapons in the temple’s inner sanctum. The idea of a gurdwara being built in honor of a person trickles down to small village gurdwaras erected in honor of a priest or significant contributor to a community, like several household gurdwaras I saw where the picture of a deceased relative sat next to the Guru Granth Sahib. Since religion, in many ways, is a process of teaching children an inherited set of values and beliefs, the story of Jorawar and Fateh Singh is particularly resonant because of how it can teach children of sacrifice and unwavering devotion to family and faith. Moreover, the chaar sahibzaade are, after the Gurus, among the first evoked in the Sikh Ardas, or major spoken prayer of the daily litany. In other words, they are among the first to be remembered:

The opening of the Ardas, from the Sikh orthodox code of conduct. The first paragraph is an evocation of the ten gurus and the sword of the tenth guru, while the second paragraph opens with a call to remember the Panj Pyare (the first five baptized Khalsa Sikhs), the Chaar Sahibzaade, and the Chalhiaa Muktiaa, or the forty Sikhs who died in battle in Muktsar protecting Guru Gobind Singh.

Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons also provide the faith with the first story it can depict on screen. The orthodox administration of Sikhism, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) prohibits live or animated depictions of Sikh Gurus or any form of divinity (similar to contemporary conservative Islam and its policing of depictions of Muhammad). For example, the SGPC in early 2015 protested Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh’s film MSG: The Messenger over the DSS chief’s claim of prophethood. Chaar Sahibzaade director, in an interview with Times of India, explained how arduous the process of approval by the SGPC was for him, saying, “I was adamant and after making 80 trips to Amritsar managed to convince them.” Baweja added, “They [the SGPC] had agreed that while I could not touch the 10 gurus, I was allowed to show the boys.” Consequently, the opening credits of Chaar Sahibzaade list several pages of permissions granted by leaders in the Sikh panth, and all images of Guru Gobind Singh, despite movement occurring around him, are static. The trailer, which first attributes the SGPC, gives a glimpse of how carefully Guru Gobind Singh (whose image is based on the already ubiquitous painted image of the Tenth) is shown in the film:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CSlNf70SFi8

(And my favorite line in the film, at 1:00 in the trailer:

Wazir Shah’s courtier: “Tuhanu mauth to dar nahi lagda?” Do you not fear death?

Fateh Singh: “Tuhanu Quda to dar nahi lagda?” Do you not fear God?)

The film, finally, brings us back to Yuba City and the following float, which uses the images of Jorawar and Fateh Singh as they appeared in Chaar Sahibzaade. Because of the SGPC’s approval of the film, any image used from the film can be treated as though it has been canonized:

A float showing cardboard cutouts of Jorawar and Fateh Singh being encased in a cardboard brick wall.

After a convoluted, zig-zaggy exposition, I am brought to the point of the post: Sikhism is a process of remembering – of remembering the name of God, the martyrs of the faith, and so on. It is not necessary to delve into Khalistan and the countless Sikhs disappeared by Indian police to bring this point across, because the sacrifices of Sikhs date back to the Gurus (Guru Arjan, the fifth, and Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth, were executed by Mughal rulers, while Guru Gobind Singh was assassinated by an Afghan). As Brian Keith Axel (2001: 151) notes in The Nation’s Tortured Body, violence against the male Sikh body – the body that has adorned turban and beard and bracelet and dagger – is akin to violence against the global Sikh body, as the devout Sikh is the image of purity. The chaar sahibzaade show that violence and the nobility of martyrdom exist deeper than in the body of the pure man, but in the even purer body of the child. The inviolable spirits of Guru Gobind Singh’s children – when their father was still the living center of the faith – gave their lives in defense of the faith: Ajit and Jujhar Singh in battle, but Jorawar and Fateh Singh without spilling a single drop of blood. However, this story and its message of sacrifice only gained as much traction as it has once it was depicted on screen; this film is not the first to depict the chaar sahibzaade, but its success among global Sikhism shows how Sikh history and hagiography have slowly been migrating to the screen. Though the lives of the gurus, too sacrosanct to be approached, remain in reproduced paintings and grandmothers’ tales, their spiritual successors may finally be portrayed in a changing medium: from story, song, and picture, to film. Because they have been digitally immortalized (in a film approved by the SGPC), these sons need not fear their story be distorted by memory.

When these images are evoked in the context of Khalistan or a diasporic parade, their significance changes. For Khalistan, Guru Gobind Singh’s four princely sons argue that self-determination is a struggle that has existed in Sikhism since the time of the gurus, predating Karnail Singh Bhindranwale in the 1980s and the Akali Dal cry for Azad Punjab (sovereign Punjab) prior to Partition. Self-determination, to the separatist, is a pillar of Sikhism. To the diaspora, however, the significance of the memory shifts. Instead of the chaar sahibzaade embodying the young blood of Khalistan, they represent the stories that Sikhism cannot let its children forget. As each generation passes its selective memory and cultural amnesia onto the next, Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons remind the faithful of everything their predecessors fought for to ensure their beliefs would survive. Orthodox Sikhism anticipated this process over 100 years ago, so Sikhism has become, consequently, a process of official memory. This meticulous process of canonizing stories has allowed the faith to retain common points of reference across countries and continents. In other words, if you evoke Guru Gobind Singh’s four martyred sons, the image that comes to mind – much like Daniel Radcliffe being the face of Harry Potter or Robert Downey, Jr., for Iron Man – will inevitably be from Harry Baweja’s animated film. The movie is the memory.